Articles

AMB - The one that got away!

Does our knowledge of his subsequent history colour our view of Matt Busby during his few years at LFC? In the words of reporters who watched him, how was he judged as a player at the time? How would we judge him if, like right-back Tom Cooper, he had been killed at the start of the war? Would he still be lauded, but on a metaphorical pedestal, rather than a real plinth? How much did he contribute as a player to the modest-level club which bought him? (The 1930s was a chaotic decade for the Reds, culminating in final league positions 9th out of 22, 10th, 14th, 18th, 7th, 19th, 18th 11th and 11th.)

Busby in action for Liverpool against Brentford on 19 November 1938

Overall effect of his acquisition

The ‘Echo’ told excited LFC fans about what they could expect from their new acquisition. ‘Matt is a beautiful stylist at half back. He is one of the best trappers of the ball the game has known, because he ‘kills’ the ball dead, yet when it suits him he can ‘kill’ the ball and proceed to propel it with one and the same notion [motion?]. He began football life in England as an inside forward, but was not successful till he took up the half-back role.’ (Liverpool Echo: March 12, 1936)

Busby’s impact was not immediately obvious. The big news story at his first match was the signing of Phil Taylor rather than Busby’s debut – losing at Huddersfield. We had won 12 of the 33 matches already played that season, drawn 7 and lost 14. With Busby in the team, we won 2, drew 5 and lost 4. It is obviously unfair to read too much into the effect one person can have, but the same pattern continued in the following season (1936/37), winning 12, drawing 7 and losing 13 of the matches in which he played. Fortunes began to turn in 1937/38, the figures being 16 wins, 9 draws and 13 losses. In the last full season before the war, Busby played in every league and cup game, resulting in 16 wins, 14 draws and 16 losses.

More telling, however, are the results of games when Busby was not playing. In 1936/37 we won only 3, drew 4 and lost 7; 1937/38 won 1, drew 5 and lost 6. (He played in all league and cup matches at the end of 1935/36, and the whole of 1938/39.)

Busby with cigarette in hand delivers a words of wisdom to Liverpool teammates.

On the pitch

The quality of Busby’s playing was widely admired even by his opponents. Spartacus Educational has descriptions of his abilities from such luminaries as Stanley Matthews, Tommy Lawton, and Wilf Mannion, the last describing him as ‘an inside forward’s nightmare’. All attest to his passing game which involved seeing moves well ahead, as well as ball control.

From 14 March 1936 to 2 September 1939, Busby shared the half-back line with twelve other players. Three, Matthew Fitzsimmons, Norman Low and Bernard Ramsden, appeared only once; John Shield made two appearances, Phil Taylor nine, John Browning and Ted Savage eleven each. Busby was at right half and much more consistency was provided by five other men who were regular partners for him, Tiny Bradshaw (40), Tom Bush (63), Jimmy McDougall (64), Jimmy McInnes (51), and Fred Rogers (70).

There were spells when the same half-back line played week after week, leading to a greater understanding of each other’s game. For example, Busby, Bradshaw and McDougall played 9 times together in the remainder of 1935/36 and 17 in 1936/37; Busby, Rogers and McInnes played together 26 times during 1938/9. On 13 March 1937, that first trio - all Scots – played Preston North End, encountering PNE’s own right-half Scot – one Bill Shankly who was there again on 3 September 1939.

During these few years, it seems to have been the playing style and character of Busby which determined how these half-back lines played. He would probably be described today as an attacking midfielder, though George Kay, whose man management he greatly admired, sometimes gave him a different role. On 5 December 1936, Busby ‘gave a grand display in his unaccustomed role of pivot’ against Wolves, for example. He was always prepared to shift position when the play required it. Against Preston (31 Dec 1938, LFC’s fifth game in ten days) ‘Busby, facing an offside net, wisely became a forward in collaboration with Nieuwenhuys and led up to the penalty by which Liverpool took the lead’. The move was repeated against Everton (4 February 1939): ‘Niewenhuys and Busby changed places in their efforts to break down Everton’s defensive barrier.’

Such a switch was not unique during the ‘30s, perhaps following Busby’s example. Nivvy’s scrapbook has a report of an Arsenal game (18 March 1939). ‘The Liverpool switch had me baffled for a time. Fagan started off at centre forward, but immediately the ball had been kicked off he dropped back and became a kind of loose foraging half-back. He left Rogers to hold the middle of the field and Balmer to do the forcing in the centre. Effective and puzzling to a defence who do not quite know who it is looking out for.’

The general picture with Busby involved, however, was of either of the two wing half-backs marauding forward, leaving the centre-half (usually Bradshaw, Bush or Rogers) to hold the fort in front of the full backs.

Busby’s leadership in attack was often praised by the commentators. ‘Matt Busby was the one man who did something to suggest first division standards. His urging of the right wing pair was of fine character, a model of priceless half-back arts – the use of the ball, the control and collection of the ball; the upward tendency to force a poor line of attackers to have some belief in themselves. It was of little use; the team was poor, and even captain Cooper had a bad game.’ (v Norwich, FA cup 3rd round, 16 Jan 1937)

‘Busby was a tireless worker, and the Leeds left wing never got out of his grip. In addition, Busby was tireless in attack, especially with the stylish and clever Eastham.’ (v Leeds, 25 Sept 1937) Two months later, v. Bolton, ‘Busby was the marshal of most of Liverpool’s attacks, and he, Rogers, and Cooper were more responsible than anyone for the hold-up…..’ Against Arsenal (18 Dec 1937), ‘Busby turned the lever in all-up attack, calling up his colleagues with low hand clapping…’ On New Year’s Day, 1938, ‘Busby was a sixth forward when things were running well for Liverpool’ providing an assist for one goal. He was an ‘inspiring’ player, exuding ‘confidence’ in his team mates, as he had done for MCFC.

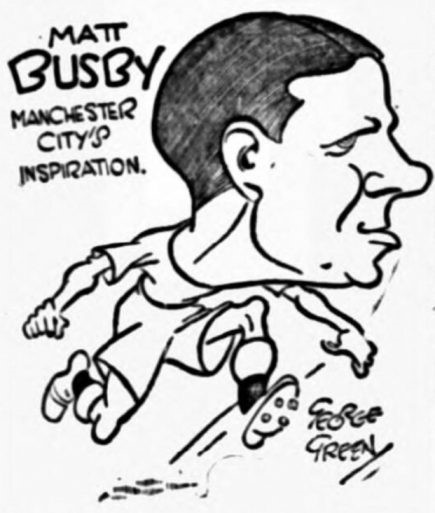

September 8, 1934

Matt Busby, Manchester City.

(Source: Liverpool Echo: September 8, 1934; we’d beaten MCFC three days earlier.)

Busby was bought as a half-back after Manchester City had already converted him (through the accident of injury) from a forward, and his value as a player had risen from £150 in 1930 to £8,000 in 1936. (Phil Taylor made the same positional switch after the war.) He clearly enjoyed his positional origins. One of his two goals for LFC came ‘when he became a forward against Charlton’ (10 September 1938) with ‘a lightning change of position’. ‘The feature of the game was the brilliant play of Matt Busby, Liverpool’s Scottish international half-back, and it was fitting that he should score Liverpool’s goal following a splendid individual effort in which he beat four men to finish up with a smashing shot from a dozen yards out which left Bartram helpless.’

‘International’ sounds good – but he played for Scotland officially only once, and that was in 1933 before Liverpool bought him. One wartime match, attracting 75,000 to Hampden Park, included Busby, Shankly and Liddell facing Lawton and Matthews. He also captained both Scotland and Liverpool in some matches during the war.

A pre-war view of his skills was repeated for one of his obituaries in 1994. ‘At best Busby has no superior as an attacking half-back. It is his bewildering footcraft which most delights the crowds. His crouching style may not be pretty but the control is perfect, the effect akin to conjuring…… His dribble is a thing of swerves, feints and deceptions. Few opponents are not hoodwinked by his phantom pass… Busby scorns the obvious. His passes not only look good, they sound good.’

His aggressive approach to the game often resulted in injury, which was, in any case, an occupational hazard for the half-back line. With no substitutes allowed before 1965, there was considerable psychological pressure to soldier on when injured, which sometimes compounded the problem. Wounded half backs were sometimes put on the forward wing where they would do less damage! On 22 January 1938, against Sheffield United, Rogers was injured at the start, and was ordered to play the rest of the match with a bloody nose at outside left. Cajoled by the crowd, he shouted, ‘I want to go back but they won’t let me’. Later in the same match, Busby ‘had to go to the line for trainer C. Wilson to bandage his right thigh. When Busby returned, he took over the outside right position’. He was not in the team for the replay four days later nor against Preston a week later because he ‘could not walk upstairs without help. But in 48 hours the stiffness may disappear’. Against Chelsea on New Year’s Day 1938, Busby, ‘hurt just before the end, insisted on remaining although he was only able to limp about the field’.

He was what is often called ‘a footballer in love with football’, an approach which coloured both his playing and managerial careers, with an attractive combination of calmness and skill which gave him a head start as captain.

The captaincy

From his debut on 14 March 1936 until the outbreak of war, LFC had six captains for league and cup games. Three of them, were ‘for emergency use only’. Tiny Bradshaw (4/9/37, when only Blenkinsop of the other five was in the team, Ernie being about to depart for Cardiff City) and ex-Scottish captain Jimmy McDougall (11/9/35) each appeared only once. Keeper Arthur Riley was captain for four games in the latter half of the 1937/38 season (29 Jan, 2 and 19 Feb., and 16 April, when none of the other five was in the team).

The other three were recognised in turn as the club (as opposed to team) captain, who took precedence even when the others were playing. When Busby arrived, Ernie Blenkinsop held the position, with Tom Cooper as his deputy. Ernie had captained England four times. From the end of September 1936, Tom Cooper was captain, with Matt Busby deputy – Ernie continued with LFC, and occasionally played under both of them.

Tom Cooper had been captain of Derby County (1931-34) and twice for England. He had deputised for Blenkinsop since arriving at LFC, especially during the latter’s spells with cartilage trouble. He remained Liverpool captain from September 1936 until the summer of 1939. (He was killed in an RTA early in the war.)

Busby himself was often team captain when Cooper was not playing, first at Maine Road in front of his old crowd on 29 March 1937, and nine subsequent times. Somewhat ironically, he was made club captain only for the three matches at the start of the 1939/40 season which are still not officially in the FA record books as having taken place. Matt sits proudly on the team photo, with Cooper literally sidelined on the far right, captain and former captain now with no matches to show for their efforts.

Busby was Liverpool's captain in the abandoned 1939/40 season

Having played well on the tour of eastern Europe and in the traditional ‘Reds v Whites’ trial game on 19 August, Busby missed a number of games at the start of the 1936/37 season, six before the end of September (LFC winning only one of them), though the press gave no explanation other than ‘Busby cannot play’ or ‘Busby will be missed’. (This gave Fred Rogers opportunities to cement a first team place, the directors realising that they did not need to buy a new player when he had done so well deputising.) Busby was also absent for four during the Xmas period, having twisted his ankle against Sunderland. In consequence he is missing from the annual photo at Stoke on Boxing Day.

Departure

To pass by Matt Busby’s wartime experiences in a paragraph verges on insulting. He spent almost twice as long in the army as he had playing for Liverpool and, like so many others in the squad, found that his professional playing career was over. His background made for an easy army decision to use him as a fitness instructor at Sandhurst. All football contracts had been cancelled, but players were encouraged to play as guests for teams nearest to where they were stationed – in Busby’s case, Chelsea, Middlesbrough, Hibs, Reading, Brentford, and Bournemouth. One source adds Aldershot to the list.

As war ended, Busby was in his mid-thirties and ready to tackle a new challenge in football. In May 1944, still on LFC’s books as a player, he was offered an assistant managerial post at Anfield after the war but, so the story goes, instead took the manager’s job at Old Trafford almost a year later where they offered him a fifty per cent rise, and more freedom to make managerial decisions than at Anfield. That simplified version of what happened does not ring true. As an assistant under George Kay, there would have been no question of him trying to negotiate the degree of ‘freedom’ from the directorial control which the post carried.

I think it is much more likely that his footballing brain had long since told him, as it would to his younger counterpart and friend Bill Shankly, that the degree to which the directors controlled the day to day running of a club, right down to team selection, was far too restricting on the manager, and he sought a route out of Liverpool to where he could properly manage the team. Yet, at that time, Manchester United was no different from Liverpool in the way the club was run.

So how did AMB become the one that got away? Enter the eminence grise behind MUFC before and between the wars, the man who claimed to have first suggested that ‘Newton Heath FC’ should change its name to Manchester United. Louis Rocca had tried to get MUFC to sign Busby from City rivals back in 1930, but they could (or would) not afford the fee. Now he wrote secretly to Busby who, he knew, was already committed to the assistant manager’s (player-coach) job at Anfield and, in more modern parlance, ‘tapped him up’. Different sources give contradictory dates to the events which followed, but the content of his letter, which Matt Busby received on 15 December 1944, survives. Rocca apologized for a short delay because he could not find Busby’s home address. The letter went via Busby’s regiment.

‘I could not trust a letter going to Liverpool, as what I have to say is so important. I don’t know if you have considered what you are going to do when war is over, but I have a great job for you if you are willing to take it on. Will you get in touch with me at the above address, and when you do I can explain things to you better, when I know there will be no danger of interception. Now Matt I hope this is plain to you. You see I have not forgotten my old friend either in my prayers or in your future welfare. ’

Meetings and phone calls must have followed, with Rocca getting the MUFC board to agree to negotiations. By 14 February 1945, when Busby asked to be relieved of his LFC contract, having received ‘other offers’, Rocca must have had all the main problems sorted. The next day Busby was announced as the new manager of Manchester United, to commence 1 October, 1945 when, technically, he was still a soldier. It followed a formal meeting with Chairman James Gibson at the latter’s factory in Trafford earlier that same day. At Manchester, even as young as 37 but aided by Rocca, he had put pressure on, as a prospective manager rather than an underling, to get his views on a manager’s role accepted by the directors because the club was in such dire straits when the war ended. He was demobbed only on 22 October, and began rebuilding the squad consisting of players largely recruited by Rocca.

Busby along with teammates Jim Harley, keeper Alf Hobson and Fred Rogers in action at Charlton on 15 January 1938.

There are other elements to colour this story. One is of religious affiliation – Busby and Rocca were both in the Manchester Catholic Sportsman’s Club. It is said that he wanted to return to Manchester where he had been a player, and that he had gone to Liverpool only out of consideration for his wife’s health. (It was reported at the time that his ‘sensational’ move to LFC ‘was at his own request’, and that MCFC had been reluctant to sell him.) The Manchester Evening News quoted United’s club secretary: ‘Busby has had a number of offers, but he approached us himself as he particularly wanted to come back to Manchester’. Various Manchester sources also claim that Busby had been offered the LFC manager’s job, which was also untrue. His role was ‘club coach’ for the development of younger players, as ‘Matt not only knows the game from A to Z, but has the faculty for conveying that knowledge to others’. He had also made a name as mentor to new players – Frank Swift at City, and Bob Paisley at Anfield.

The one that got away (cynics might say ‘ran away’) became Manchester’s hero, while the club he left fell from the top of Division 1 to relegation a few years later until we lured our own Scot, aged 46, to save us by ‘tapping him up’ at Huddersfield Town. It has been argued that Manchester’s acquisition of Busby was one of the origins of the rivalry between the two clubs. Until then, Everton had always generated larger Anfield crowds than MUFC had done, but in 1948/49 three thousand more turned out to see Busby’s team than that of Cliff Britton.

Busby’s short length of service at Anfield, perhaps, prevents him being one of our greatest players, but while still at Liverpool, not yet tainted by his later career, there is no doubt that he was not just liked but greatly admired for his footballing skills. The Liverpool Echo summed it up in a 1941 …. ‘There is and only will be one Busby’, and the Evening Express (13 May 1944) averred that Liverpool ‘have never made a better investment’ than to sign Matt Busby. It seems probable, on the evidence above, that during his relatively short time at the club, LFC was not good enough to exploit fully his undoubted talents, either on the pitch or in the boardroom. With hindsight, I wonder if he could have done a better job at Liverpool than Shankly did. We’ll never know, so why bother even thinking about it!

Dr. Colin Rogers for LFChistory.net