Articles

Paul Tomkins on Bill Shankly

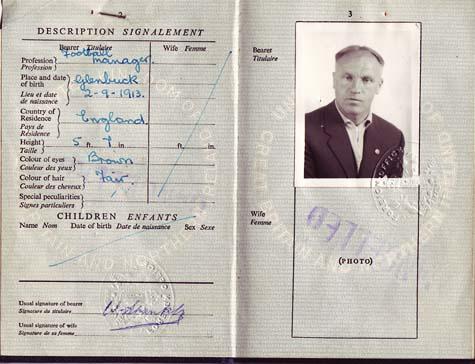

Shankly's passport was well worn after the club's many European travels

A handful of years after the game, evidence of the systematic bribery of Italian officials emerged, with many of the accusations centring around Inter Milan between 1964 and 1966. According to the testimony of a number of officials, Dezso Solti, a Hungarian fixer, worked with Inter’s secretary Angelo Moratti to entice referees to corrupt the result in Inter’s favour. The year before Liverpool’s night of despair, Borussia Dortmund had a key man sent off in a semi-final at San Siro, while in 1966 the linesman Gyorgy Vadas claimed he was “offered enough dollars to buy five Mercedes” to help Inter overcome Real Madrid in the European Cup Final. So it stands to reason that the same efforts were being made in 1965. Perhaps most interesting is how Tommy Smith assaulted de Mendibil just after the final whistle, but the referee, who now had good cause to punish Liverpool, simply ignored it. Perhaps his sudden sheepishness was borne out of guilt, and a need to have the game end without a red card, the cause of which would need explaining. “I hoofed him in the left ankle,” Smith recalled, “but he just kept on walking, just as he did when I was screaming ‘el bastido’ at him.”

The second European lesson, 18 months later, was received from an up-and-coming Ajax side who would go on to become legends. As such, it’s hard to say which lesson was the more galling to Shankly — being cheated, or being outclassed. Liverpool went to Holland in the second round of the competition and on a foggy night were on the receiving end of a 5-1 drubbing. The star of the show was 19-year-old Johan Cruyff. Shankly, in ebullient mood, felt the deficit could be overturned in the return leg at Anfield, but Cruyff, dubbed “Pythagoras in boots” by the sportswriter David Miller due to the angles he could spot, scored twice as Ajax drew 2-2. Shankly learned a lot from Dutch, which served him good stead as he began building the second great team from the late ‘60s onwards.

Crowning Glory

In 1973, Liverpool became the first English team to win a European trophy at the same time as landing the English league crown. But was it Shankly’s greatest achievement? What about getting the team out of the old Second Division? Or winning his first league championship? Then there was beating Leeds in the 1965 FA Cup Final, at a time when it was seen as the most important day in the English football calendar. Any of these feats would be worthy of recognition, but the then-unique double of 1973 stands out, given that it was also achieved with a rebuilt side.

Legacy

While he may have regretted resigning almost as soon as the ink was dry on Bob Paisley’s managerial contract, Shankly left the club in great health. Having only recently rebuilt his side, there were only two players — Callaghan and Lawler — on the wrong side of 30. The foundations were set for Paisley to take things to an even higher level. Paisley’s job would have been that much harder had Shankly not had the foresight to sign so many talented young players to replace his first batch of stars.

Above all else, Shankly, aided by the men alongside him, was an innovator. Liverpool did not stick with tried and tested, and Shankly wasn’t positing the methods and techniques of the 1930s. He took the club forward with foresight; unfortunately, part of the legacy of his success was that it became extremely difficult for subsequent managers to introduce new techniques, so successful had his own proven.

Transfers In

In many ways Shankly’s signings were the most mixed of any Liverpool manager. There were a high number of resounding successes — the names now prominent in the club’s folklore — but also, despite trophies making them easier to forget, an equal number of flops. The successes clearly obviated the need to rely on the flops. After all, it’s not the signings a manager gets wrong that count when silverware is accrued, but the ones who contribute to that success. Getting the right players was a serious business to Shankly, and a lack of backing from the board tempted him to resign on a number of occasions. Ray Wilson, the England World Cup winner who made his start in the game under Shankly at Huddersfield, said “You felt Shankly was the only manager in the world who might spend his own money to buy players.”

It started so inauspiciously for Shankly at Liverpool, with the transfer of Sammy Reid from Motherwell. Reid, who cost £8,000, never played a single game for the club. Kevin Lewis, signed from Sheffield United, was an altogether better signing. He cost a club record £13,000 in 1960 — 20% of the overall English transfer record at the time. Lewis, a tricky winger who was still not quite 20, went on to score 22 goals in his first 36 games, and was an important part of the team that finally escaped the second tier of English football. Once promoted to the top flight, he scored ten goals in 19 First Division matches, but was sold to Huddersfield in August 1963 for £18,000.

Two months after landing Lewis, Shankly broke the club record again to sign Gordon Milne from Preston for £16,000. Milne, the son of Shankly’s friend and former colleague Jimmy, and known to the Liverpool manager since birth, went on to play almost 300 games for the Reds. As a result of his form at Anfield he was capped 14 times by England; he was in Alf Ramsey’s provisional 27-man squad for the 1966 World Cup but missed the cut when it was reduced to the final 22. In 1967, at the age of 30, he was sold to Blackpool for £30,000 — a substantial fee for a player in the twilight of his career.

Promising striker Alf Arrowsmith, aged 17, cost just £1,250 from Ashton Utd in August 1960. He initially developed his scoring instincts in the reserves, netting 65 times in two seasons. By 1963/64 he had broken into the first team, and scored 15 goals in 20 league games as the Reds won their first league title for 15 years. But a serious knee injury sustained in the ensuing Charity Shield limited his effectiveness, and he started only 19 games in the next four years before being sold to Bury for £25,000 at the end of 1968. Although it didn’t quite work out as anticipated after he burst onto the scene in such spectacular fashion, Arrowsmith proved to be a shrewd investment.

The next key signing came in July. Liverpool agreed to pay Dundee Utd £30,000 for 23-year-old centre-back Ron Yeats. As with St John, Shankly had coveted Yeats in the past, hoping to sign him years earlier at Huddersfield. Yeats became the Reds’ captain, and spent ten years at the heart of the defence, playing 454 games and scoring 16 goals. No-one has captained the Reds for as long as Yeats did — wearing the armband for almost a decade. In 1971 he was released, and moved to Tranmere Rovers.

Teenager John Sealey arrived on a free transfer from Warrington in January 1962; he played just one game, three years later, and although he scored he was released in 1966. Jim Furnell, the Burnley keeper, was signed for £18,000 in February, and took over from Bert Slater as the Reds won promotion. The emergence of Tommy Lawrence shortly after would lead to Furnell being sold to Arsenal for £15,000 18 months after his arrival.

Skilful left-midfielder Willie Stevenson was purchased from Rangers for £20,000 in October. Almost 23 when he signed, Stevenson went on to play 241 games, scoring 18 goals, before the arrival of Emlyn Hughes made him surplus to requirements. Shankly sold Stevenson to Stoke, for £48,000, in 1967. He had been a key element in the successes of the ‘60s, and the profit only highlighted what an astute signing he was.

Shankly then went out and bought a Thomson and a Thompson. The first, Robert, was a £7,000 capture from Partick Thistle in December 1962. The full-back spent two-and-a-half years at Anfield, but only made eight appearances before being sold to Luton for £3,000. The second, Peter Thompson, proved an entirely different proposition. In August 1963 Shankly paid £37,000 for the fast and tricky Preston winger, still only 20, who had previously been courted by Juventus. Thompson played 416 games in nine years at Liverpool, scoring 54 goals. But Thompson almost sabotaged his move to Anfield. “I had a friend whose father was a coach at Preston and he told me to ask for signing-on fee,” he recalled. “It was illegal at the time, but I knew a lot of players who’d got one.” Shankly was not at all pleased. He turned to club chairman Tom Williams and snapped: “I don’t want him. There’s a flaw in his character.” Thompson quickly insisted he was only joking, and Shankly withdrew his objection. “My whole body was shaking and I couldn’t sign quick enough,” Thompson said. “I never got a signing-on fee, but I was so relieved just to have completed the move in the end.”

Reserve keeper William Molyneux arrived in November 1963 on a free transfer, but was released four years later after just one game. Then, in May 1964, Phil Chisnall became the last player Liverpool signed from Manchester United. Costing £25,000, he only played nine times and was sold to Southend for £12,000 three years later. Another 1964 signing, Geoff Strong was bought from Arsenal for £40,000. Brought in as a forward to replace the injured Arrowsmith, the 27-year-old ended up playing in virtually every outfield position in his six years at the club, ending up at left-back in his last two seasons following Gerry Byrne’s retirement. Strong was sold to Coventry for £30,000 in 1970, a very substantial fee for a player aged 33.

Following a few successes, Shankly’s next four signings proved a rather more mixed bag. John Ogston can be exempted, as a keeper bought as back up, costing £10,000 from Aberdeen in September 1965. Peter Wall, who cost £6,000 from Wrexham in October 1966, was a full-back who played 42 games in his four years at Anfield, before being sold to Crystal Palace for a good fee: £35,000. But Stuart Mason, signed from Wrexham at the same time, never made an appearance after his £20,000 move. David Wilson, a £20,000 purchase from Preston in February 1967, was another failure, returning to Deepdale a year later for just £4,000 at the age of 26.

But after a run of signings that never made the grade, Shankly secured one of his greatest: Emlyn Hughes. Shankly had previously bid for the teenager following his first game for Blackpool, offering £25,000 on the spot. Blackpool, then a top flight club, were not willing to sell, but a year later, in February 1967, with the Lancashire club facing relegation, they asked for £65,000 –– far more than anything Liverpool had ever paid. Shankly had no doubts, and a deal was quickly struck. Hughes, just 19, had played only 28 games for Blackpool. Within weeks he was making his Liverpool debut in midfield, although he was an incredibly versatile player, going on to play at centre-back and left-back. An ebullient character, Hughes earned the nickname ‘Crazy Horse’ after an illegal rugby tackle on Newcastle United winger Albert Bennett. In total he’d make 665 appearances in a variety of positions, scoring 49 goals.

Having paid a club record fee for Hughes, Shankly would top it with his next purchase — albeit a far less successful one. However, the failure — Tony Hateley, who cost £96,000 in June 1967 — was followed by the arrival of another legend in the making. In a bizarre sequence, Shankly then broke the club record again, on another expensive mistake, in Alun Evans, before bringing in another of Anfield’s enduring names in Alec Lindsay. His forays into the transfer market at this time were hugely mixed, but of course, the overriding factor was that the good purchases ensured success at Anfield for years to come.

Hateley did okay, and scored a more than respectable 28 goals in his 56 games, but he did not suit the Reds’ style of play. A big, powerful centre-forward, he looked awkward in possession and out of place. A year later he was sold to Coventry for £80,000. But soon after signing Hateley, Shankly had moved to secure the services of Scunthorpe’s young goalkeeper, Ray Clemence, for £18,000. Clemence, about to turn 20, made his debut a year later, but had to wait three years to fully displace Tommy Lawrence. Once he did, he would go on to become a Liverpool legend, registering 335 clean sheets in 665 appearances. He played an astonishing 337 consecutive games from September 1972 until March 1978. In 1981, when about to turn 33, he was sold to Spurs for £300,000 — 20% of the current English transfer record, but a far bigger fee in real terms when considering his age. He is widely regarded as the Red’s best-ever goalkeeper.

Having spent £110,000 on Alun Evans, only for the youngster to fail to live up to his potential, Shankly signed Alec Lindsay from Bury for £67,000. Arriving in March 1969 at the age of 21, Lindsay originally struggled in his left-midfield role, and even had a transfer request accepted, before finding success when moved to left-back. From there he displayed his strong attacking abilities as, in the Liverpool way, he overlapped down the flank. He played 248 times for the Reds, scoring 18 goals, before being sold to Stoke for £20,000 in 1977, at the age of 29.

Another wise investment came in the April of 1969, when Larry Lloyd, a centre-back in the mould of Ron Yeats, was bought from Bristol Rovers for £50,000. Lloyd lasted five years at the club; having lost his place to the more mobile and skilful Phil Thompson in 1974 he impetuously handed in a transfer request, and was sold to Coventry for a hefty £240,000. But Lloyd’s career would undergo a remarkable renaissance years later, ending up as a double-European Champion with Nottingham Forest.

Continuing his run of successes and flops, in the spring of 1970 Shankly spent £57,000 on Jack Whitham, who failed to make the grade after moving from Sheffield Wednesday. The deal was quickly followed by the free signing of Steve Heighway from Skelmersdale, a far more inspired move. Whitham wasn’t a bad player, and scored seven times in his 18 appearances, but injuries curtailed any real progress he might have made. He left for nothing four years after arriving. Heighway’s story, however, could not have been more different. He made his debut later in 1970, and spent eleven years at the club, playing 475 times and registering 76 goals. An exciting winger with pace and an unusual gait that made his intentions hard to read, he was already 22 when he arrived from non-league football. Bob Paisley released him in 1981, when Heighway, by then aged 33, moved to play in America, before returning to Liverpool as head of youth development five years later.

Steve Arnold, signed from Crewe for £12,000, only made two appearances for the Reds, one of which was in a heavily ‘rotated’ side when Shankly made ten changes for a league game at the end of 1972/73, with two important cup fixtures still remaining. Arnold was released to Rochdale shortly after. But another signing from 1970 proved to be a resounding success: John Toshack. The big Welshman, who cost £110,000 from Cardiff, played 247 games in his seven and-a-half years at Anfield, and scored a respectable 96 goals. But it was more for how he linked with Shankly’s next signing — and arguably his best — that Toshack is best remembered. Kevin Keegan cost just £33,000 from Scunthorpe in May 1971. Keegan proved nothing less than a sensation during his six years on Merseyside.

Steve Arnold, signed from Crewe for £12,000, only made two appearances for the Reds, one of which was in a heavily ‘rotated’ side when Shankly made ten changes for a league game at the end of 1972/73, with two important cup fixtures still remaining. Arnold was released to Rochdale shortly after. But another signing from 1970 proved to be a resounding success: John Toshack. The big Welshman, who cost £110,000 from Cardiff, played 247 games in his seven and-a-half years at Anfield, and scored a respectable 96 goals. But it was more for how he linked with Shankly’s next signing — and arguably his best — that Toshack is best remembered. Kevin Keegan cost just £33,000 from Scunthorpe in May 1971. Keegan proved nothing less than a sensation during his six years on Merseyside.

Frank Lane, signed from Tranmere for £15,000 in September 1971, was another back-up keeper. He only played twice for the club, but that was enough — on his debut he had the ignominy of safely catching a deep cross from Derby’s Alan Hinton and then stepping backwards over his own goal-line. He was released in 1975. Central defender Trevor Storton, 22, was purchased from Tranmere for £25,000 in July 1972. He never made much of an impact, playing just 12 times, only five of which were in the league. In 1974 he moved to Chester for £18,000, and made 396 appearances for them in the lower divisions. Returning to players with real class, Shankly snapped up Peter Cormack from Nottingham Forest for £110,000. Recommended to Shankly by his brother Bob, who was in charge of Cormack during his days managing Hibernian, the 26-year-old was a skilful midfielder with an eye for an incisive pass. He was sold to Bristol City for £50,000 in November 1976, after 26 goals in 178 games.

In March 1973 Peter Spiring arrived from Bristol City, costing £60,000, but never playing a single game for the Reds — only twice making the bench. Spiring moved to Luton 18 months later for £70,000. Shankly then returned to the local game, as he had with Heighway, when picking up 19-year-old Jimmy Case from South Liverpool for an almost insulting £500. In 1981, after 46 goals in 279 games, Case was sold to Brighton for 7,000 times that amount. A ferocious competitor with a fierce shot, Case was one of the few players who excelled after being moved on from Anfield.

Shankly concluded his business with two more mixed signings. The first, Alan Waddle, was a 19-year-old signed from Halifax Town for £40,000 in June 1973. Waddle, the cousin of ‘80s England international Chris, played 22 games in his four years at Liverpool and only scored one goal — albeit a special one: the winner in a Merseyside derby. He was sold for £45,000 in 1977, and although that technically resulted in a profit, inflation in transfer fees meant otherwise. But Shankly bowed out on a high in terms of transfers — signing Ray Kennedy from Arsenal for £180,000, before swiftly resigning. At first Kennedy, bought as a bustling centre-forward, looked like another fairly expensive flop, but in time he proved to be one of the real stars of the ‘70s, after Bob Paisley reinvented him as a left-midfielder. Blessed with strength and stamina, as well as a cultured left foot, Kennedy scored 72 goals in just shy of 400 games for the Reds. He was sold in January 1982 for £160,000, at the age of 30; unbeknown to anyone at the time, Parkinson’s Disease had started to ravage his body and had already began affecting his game; without which he may have lasted even longer at Anfield. But as it stands, he is deservedly recognised as one of the club’s true legends.

Transfer Masterstroke

Ian St John? Ron Yeats? Ray Clemence? Emlyn Hughes? Steve Heighway? Ray Kennedy? A case can be made for all of the aforementioned when it comes to Shankly’s best signing. But given the cost, where he was found, the impact he made, and how far he progressed –– not to mention the fee he eventually left for –– it has to be Kevin Keegan. Recommended to Shankly by Andy Beattie, a former colleague at Preston, Keegan was playing at lowly Scunthorpe United. Shankly sent chief scout Geoff Twentyman to check him out. Twentyman liked what he saw, and wrote up a positive report on the player. Incredibly, Shankly never even went to watch Keegan; as soon as Preston bid £25,000 he knew it was time to make a move. In May 1971 Liverpool agreed to pay £33,000 for the youngster, who had recently turned 20. Keegan was taken to the FA Cup Final against Arsenal that month, purely as a spectator; Shankly was instantly impressed with how hard Keegan took defeat — he’d only been at the club a matter of days and already he was taking it personally. Having impressed in the reserves, he made his first team debut in August 1971, starting against Nottingham Forest; within twelve minutes he’d scored the game’s opening goal. He went on to score exactly 100 goals in his 323 games for the Reds. An English record transfer fee of £500,000 saw him move to Hamburg in 1977.

Expensive Folly

Alun Evans appeared to have it all when he signed for Liverpool in 1968 at the age of 19. He cost a massive £110,000 — an English record for a teenager — and started off brightly, scoring on his debut against Leicester City, a game Liverpool won 4-0, with all the goals scored in the opening 12 minutes. Evans scored six more times in a total of 33 league appearances that season. But he didn’t maintain that promising start, and was never the same player after being attacked with a broken glass in a nightclub in 1971, an incident that left him facially scarred.

A year later Aston Villa paid Liverpool £72,000 for Evans, who was still only 23. Never a total failure at Anfield — he scored 33 goals in 111 appearances — he failed to reach the heights expected of him, and given transfer fee inflation, was sold for a significant loss.

One Who Got Away

Shankly’s first thought when it came to strengthening Liverpool was to go back to Huddersfield for his teenage prodigy, Denis Law. The striker, about to turn 20, was not only out of Liverpool’s price range but was also destined for a First Division club — not one languishing in the second tier of English football. Shankly enquired, but the Reds would only have been able to stretch to £20,000; a couple of months later, Law was sold to Manchester City for £55,000, a new English transfer record.

Another early target was the Leeds United defender, Jack Charlton. The tall centre-back — the elder brother of England and Manchester United starlet Bobby — was a tough, no-nonsense character with an eye for goal. (While Bobby made his name as a goalscorer, Jack registered almost 100 league goals, virtually half the total of his more illustrious and attack-minded sibling.) Shankly made two approaches for Charlton, and on the second occasion he felt he could get his man following Leeds’ relegation; but the Liverpool board would not meet the asking price, refusing to go above £18,000, when the fee quoted was almost double that. Five years later Charlton, who remained at Leeds for his entire playing career, became an England international and was part of the World Cup-winning side. Fortunately, Shankly had by that time found an imposing centre-back in the form of the ‘colossal’ Ron Yeats.

Brian Clough, who eventually moved from Middlesborough to Sunderland for £45,000, was a striker Shankly was extremely keen on landing in his first year at Liverpool. Unfortunately Clough, whose career statistics were quite staggering –– 197 goals in 213 league games for Boro –– was well beyond Shankly’s budget. Clough went on to score 54 goals in 61 games for Sunderland, but his career was effectively ended at the age of 27 when he ruptured his cruciate ligament; his return, aged 29, lasted just three games. Had he joined Liverpool, that particular collision would not have taken place; and had he avoided a similar injury, he wouldn’t have taken up management at such a young age. And had he not been an established manager by the age of 30, it’s unlikely he would have been making life tough for Bob Paisley’s Liverpool a decade and a half later. So stumping up £45,000 might have been a ridiculously good bit of business! Of course, neither party could have any great regrets, given the way history panned out for both Liverpool and Clough.

In March 1967 Shankly was desperate to land Preston’s Howard Kendall. Instead, Kendall was sold to Everton for £80,000 — the Deepdale club were keen to not sell a third talent to the Reds following on from Peter Thompson and Gordon Milne. Shortly after, Shankly inquired about Francis Lee, a slightly rotund 23-year-old forward at Bolton. “I recommended Francis Lee to Bill in my first week at the club,” explained Geoff Twentyman. “I’d seen him play and thought, here’s a great one for the future.” Two months later, in October, he was sold to Manchester City for £60,000, where his reputation grew, along with his waistline. By the start of the ‘70s, Shankly had his heart set on Peter Osgood, the Chelsea striker. He offered £100,000, and when it was rejected, returned with a massive offer of £150,000. Again he was waved away, and Shankly left it at that. Four years later Osgood, then aged 27, joined Southampton for £275,000.

Frank Worthington was another major missed target, this time in the most comical of circumstances. Worthington, a 23-year-old maverick talent making waves at Shankly’s old club Huddersfield, was all set to move to Anfield for £150,000 –– a fee that would have made him the third most expensive striker in Britain. With the deal agreed, Liverpool had to wait to complete the formalities due to Worthington’s presence on an England U23 trip. Peter Robinson met Worthington at Heathrow and took him to a nearby hotel to meet Shankly. Worthington liked what he heard, and agreed terms. The next day, back at Anfield, the contract was signed. All that remained was the medical — which he promptly failed due to high blood pressure. Worthington was known to like the high life, and was already developing a reputation as a womaniser. But his father had recently died, and it had been a stressful time for the young man. Shankly, concerned for the player’s well-being, sent Worthington on a week’s holiday to Majorca, to rest and reduce his stress levels. Despite dizzy spells and passing out in his hotel room while in Spain, rather than rest, Worthington was out enjoying the night life. Upon his return, Shankly could barely believe it: Worthington’s blood pressure was even higher. Worthington promptly moved to Leicester City, but lacked focus throughout the rest of his career. Hindsight suggests he wasn’t what Liverpool needed, as the Reds prospered without a player who was failing to live up to his enormous potential, but maybe Liverpool could have given him the discipline he needed.

Frank Worthington was another major missed target, this time in the most comical of circumstances. Worthington, a 23-year-old maverick talent making waves at Shankly’s old club Huddersfield, was all set to move to Anfield for £150,000 –– a fee that would have made him the third most expensive striker in Britain. With the deal agreed, Liverpool had to wait to complete the formalities due to Worthington’s presence on an England U23 trip. Peter Robinson met Worthington at Heathrow and took him to a nearby hotel to meet Shankly. Worthington liked what he heard, and agreed terms. The next day, back at Anfield, the contract was signed. All that remained was the medical — which he promptly failed due to high blood pressure. Worthington was known to like the high life, and was already developing a reputation as a womaniser. But his father had recently died, and it had been a stressful time for the young man. Shankly, concerned for the player’s well-being, sent Worthington on a week’s holiday to Majorca, to rest and reduce his stress levels. Despite dizzy spells and passing out in his hotel room while in Spain, rather than rest, Worthington was out enjoying the night life. Upon his return, Shankly could barely believe it: Worthington’s blood pressure was even higher. Worthington promptly moved to Leicester City, but lacked focus throughout the rest of his career. Hindsight suggests he wasn’t what Liverpool needed, as the Reds prospered without a player who was failing to live up to his enormous potential, but maybe Liverpool could have given him the discipline he needed.

Celtic’s attacking midfielder Lou Macari, 24, was another one of those deals that was struck, only to fall through at the 11th hour. A £200,000 move had been agreed with the Scottish giants in January 1973, and Macari was invited down to Anfield, where he was guest of honour for an FA Cup game. However, he dallied over signing, and Manchester United came in and offered him more money. He promptly signed for them, and four months later they were relegated — while Liverpool won the league. “He couldn’t play anyway. I only wanted him for the reserve team,” Shankly told his players.

But there was one far more special player, who, like Macari, had Celtic connections but slipped through Shankly’s grasp: one Kenneth Mathieson Dalglish. It was 1966, and Dalglish was a 15-year-old schoolboy arriving at Anfield for a trial. He played one game, for the B team against Southport Reserves in the Lancashire League. Liverpool won 1-0, but no further interest was expressed by the club. Years later, when Shankly saw the youngster play for Celtic, for whom he’d signed in 1967, he was livid, blaming his own club’s scouts for letting such a great player slip through the net. He claimed he had no idea the player had been at Liverpool for a trial. But in his autobiography, Dalglish claimed that Shankly and Reuben Bennett had given him a lift back to the YMCA where he was staying after the match. Thankfully, Bob Paisley went out to remedy the situation eleven years later, but for an English record transfer fee. It cost a small fortune, but it all worked out fine in the end.

Budget — Historical Context

Manchester United obviously had to rebuild after the Munich air crash in February 1958, so it’s a little unfair to be too critical of their spending during Shankly’s early years. Of course, in the same period, Liverpool’s team also needed rebuilding, albeit for very different reasons. Of the eight who perished on the German runway, six — Duncan Edwards, Tommy Taylor, Liam Whelan, Eddie Colman, Roger Byrne and David Pegg — were key players, while Jackie Blanchflower survived but never played again. Immediately after the crash, Matt Busby bought Ernie Taylor (£8,000), Stan Crowther (£18,000) and Albert Quixall (£45,000), but several important players, including Bobby Charlton, Bill Foulkes, Harry Gregg and Dennis Viollet were still part of the team, having survived the disaster. Johnny Giles made his debut in the immediate aftermath.

Between December 1959, when Shankly took charge of Liverpool, and 1964, when the Reds were crowned Champions, United signed the following players: Maurice Setters (£30,000), Tony Dunne (£5,000), Noel Cantwell (£29,500), David Herd (£35,000), Denis Law (£115,000), Pat Crerand (£56,000), Graham Moore (£35,000), John Connelly (£60,000) and Pat Dunne (£10,500) — a total of £376,000. In that same period, Liverpool paid out £196,750 –– just over half as much. However, the United team that won the 1968 European Cup was comprised largely of home-grown talents; shorn of injured record-signing Denis Law, it cost on average only 10% of the English transfer record. As happened at a number of clubs over the following decades, success came not at the time of spending big, but a few years after, when promising young players came through the ranks.

The Leeds United that overtook Liverpool in the late ‘60s was another comprised mostly of youth team graduates. Of the team that won the 1970 FA Cup, Gary Sprake, Paul Madeley, Terry Cooper, Billy Bremner, Jack Charlton, Norman Hunter, Peter Lorimer and Eddie Gray all started out at the club. Leeds had paid £37,500 for Manchester United’s Johnny Giles in 1963, and towards the end of the decade their two strikers — Mick Jones and Allan Clarke — had cost a whopping £100,000 and £165,000 respectively. But the average was still only 21.4% of the English record — even though they themselves set that high-water mark in 1968 when snaffling ‘Sniffer’ Clarke.

The Liverpool side that beat Leeds in the 1965 FA Cup Final, and which was behind the league successes either side — Lawrence, Lawler, Byrne, Strong, Yeats, Stevenson, Callaghan, Hunt, St. John, Smith and Thompson — averaged out at just 13% of the English record.

Record

League Championships: 1963-64, 1965-66, 1972-73

FA Cup: 1965, 1974.

UEFA Cup 1973.

Division Two Championship: 1961-62.

P W D L F A %

Overall 783 407 198 178 1307 766 51.98%

League 609 319 152 138 1034 622 52.38%

FA Cup 75 40 22 13 103 50 53.33%

League Cup 30 13 9 8 51 35 43.33%

Europe 65 34 13 18 114 54 52.31%

Conclusion

Whether or not Shankly was the best Liverpool manager will always be open to debate and conjecture. But there can be no doubting that he was the most important. It’s like the first goal in a 3-0 victory — it needs to be scored before the others can follow. The second adds breathing space, and the third kills off the opposition’s hope of a recovery. But the game is shaped by that first goal.

Or, to use an obvious metaphor, a house cannot be built until firm foundations are laid. If subsequent managers added extra storeys and extensions, they nonetheless all relied on the strength that underpinned it all. And that entire base was courtesy of the work undertaken by Shankly, as he changed the entire culture of the club.

Following his shock retirement in 1974, Shankly felt somewhat ostracised by the club. In later years he had to buy tickets to away games, and claims he wasn’t treated with the respect he felt he deserved. A testimonial took place in 1975, and that netted him £25,000 as 40,000 fans flocked to Anfield to say their thanks. In many ways the club was moving on, just as it did when players left. But it clearly hurt the man who had done so much to rouse the sleeping giant. Six weeks after retiring he knew he’d made a terrible mistake; but by then the club was moving on without him. He asked John Smith if he could return, after his short break had left him feeling refreshed — not to mention lost, without the daily routine — but it was now Bob Paisley’s team. He loved football with an incredible passion, and missed it terribly. “If there wasn’t football at Liverpool he’d go to Everton,” said Tommy Smith. “If there wasn’t football at Everton he’d go to Manchester. If there wasn’t football at Manchester he’d go to Newcastle. If there was nothing on he’d go to the local park and watch two kids kicking a ball. If there were no games on he’d organise one.”

Shankly’s death, in September 1981, was felt deeply on Merseyside. Aged 68, and having looked after himself fastidiously, he succumbed to a serious heart attack, while in hospital recovering from a minor one. The news reduced Paisley, Fagan and Moran to tears, and training was cancelled. Across the city, flags flew at half-mast. It was as if royalty had passed away. He loved Liverpool, and the fans he made so happy for so long, loved him in return.

Perhaps it’s best to use the great man’s own words to sum up his time at the club. “What I achieved at Anfield,” he once said, “I did for those fans. Together we turned Liverpool into one huge family, something alive and vibrant and warm and successful.”

Copyright - Paul Tomkins