Articles

A record to forget - Liverpool’s only yo-yo.

About the time that Liverpool FC was created in 1892, major changes were happening to the way first class football was organised in England. The Football League itself, founded in 1888, comprised entirely of a dozen clubs from the industrial centres of the north-west and midlands, while a separate Southern League began in 1894. There was no second division until 1892/93; before that, clubs in what we would regard as a relegation zone were normally, and formally, re-elected to the League for the following season, unless they dropped down to a less prestigious organisation. All twelve clubs were re-elected to the Football League at the end of the 1890/91 season. The original dozen Football League members increased to sixteen, but once a second division began, absorbing an existing, unconnected, Alliance League, a decision had to be made as to how movement between the two levels was to be decided. Few people, if any, spoke against the principle of such movement, but there was argument and dissatisfaction about how it was first arranged.

Taking a phrase from other sports, a ‘test match’ system was introduced, in which the three bottom clubs from Division 1 and the three top clubs from Division 2 fought it out, the three winners being elected to Division 1. As a reward for being the ‘best of the worst’, the top of Division 2 was pitted against the bottom of Division 1, second best against second bottom, and third in Division 2 played third from bottom in Division 1. Thus, each of the six clubs involved would play only one test match, the results determining whether they could be elected to a new division or remain where they had been already. In addition to simplicity, this arrangement had other advantages – for example, playing in a neutral stadium, and (after 1896) with a referee who was not from either team’s area. As these matches were additional to the League schedule, the clubs concerned all gained financially – as many as 30,000 spectators paid to see the test matches in 1896 – and, at first, all on a Saturday afternoon to accommodate the newly developing practice of working only until lunchtime. It also modified the system of election to a division, which was seen as open to outside influence. ‘Is it not merely a question of who has most friends at court?.....there is no merit in being able to influence a certain number of votes’ (Morning Leader 28/4/94).

Liverpool Echo report on Liverpool - Newton Heath (future Manchester United) in April 1894.

Clubs like Newton Heath could no longer remain unchallenged at the bottom of the League year after year. The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News 28/4/94 wrote, ‘Newton Heath has been the absolute last of the first division for two seasons in succession, and Darwen has always figured at the wrong end of the list; neither is good enough for the place, and they “never will be missed” if they have to give way to Liverpool and Small Heath’ (the future Birmingham City). ‘They should find themselves quite at home in the lower grade of the League’ (Black and White, same date).

Test matches were not to everyone’s liking, although that’s not why they lasted only five seasons. There is often reference to the poor quality of football, the blame falling squarely on the importance of the game. ‘Extreme rivalry……served to make the game not too free from roughness’, reported the Newcastle Daily Chronicle. In one instance, even a goalkeeper was sent off for kicking a Liverpool player in the stomach. In Liverpool’s game against Newton Heath, ‘too often the players went for each other when there was no necessity’ (Athletic News).

The Lancashire Evening Post echoed another objection to the test match scheme.

All members of the Football Association had been able to enter the FA Cup competition since 1871, but commentators found it hard to accept that a club which won the FA cup should not be in the top division. In 1892, West Bromwich Albion even avoided having to be re-elected because they were the cup winners that year. The London-based, influential Morning Advertiser carried the following shortly after the 1894 test matches.

Another objection to these early tests could not be expected to arouse the sympathy of the modern Liverpool fan. As a result of knocking Newton Heath into Division 2, the system was then blamed for giving the city two clubs while depriving Manchester of any first-class football!

*

Liverpool’s own distinctive passage through the ‘dreaded ordeal’ of the 1890s’ tests began at Blackburn on 28 April 1894. After early success in the Lancashire League in 1892/93, they had been accepted into Division 2, where they lost none of their twenty-eight League games. Promotion was not guaranteed even then, and thus the neutral venue Ewood Park witnessed the first encounter of the future Liverpool and Manchester rivals, this time fighting for Division 1 election through a test match.

An estimated 5,000 crowd, about half from each city, saw an uneven contest, Liverpool having three times more shots on goal, combining together better and playing faster and smarter than the ‘Heathens’. The result had been widely predicted in both England and Scotland, where interest reflected the number of Scotsmen playing for Liverpool. Brief notices of the game appeared all over the country, often syndicated.

Details, as reported by the Liverpool Echo and the Liverpool Mercury (the latter particularly gushing in its praise for the winners), are available in lfchistory.net’s game summary. Differences in the anticipated thirst for information in the two cities found their way into the texts. The Manchester Courier covered the match in only 32 lines – even the Sheffield Daily Telegraph report occupied twice as much - mentioning the Newton Heath defence rather than the Liverpool attack.

The more independent Athletic News (notwithstanding being published in Manchester) added assessments of individual players, concluding that ‘the defeat can in no way be attached to [Falls, the Heathens’ goalkeeper] for he cleared and kicked well…..; on the day’s play, Liverpool deserved their victory.’ Of Newton Heath’s players, centre-forward Donaldson was ‘about the best of the lot, and even he was no great shakes’. On the other hand, McQueen (Liverpool’s stand-in goalkeeper) ‘had very little to do owing to the fine defence of the backs……… the half backs were strong, McBride being by far the pick of the three, but the marked superiority was in the forward division, the winners’ quintette being sharper and shooting far better than those of the other team.’

Part 1 of the triple yo-yo thus concluded, we run at once headlong into a pattern with which we have recently all become familiar – the promoted club syndrome. The gap in quality between the two divisions (Newton Heath were third in Division 2 in 1894/95) was exposed when Liverpool immediately ran into trouble. They had to wait until near the end of October for their first win; the second was on 15 December, against Stoke and Birmingham respectively. Five more wins in the new year completed a dreadful League campaign. We were the only club in the League to lose twice as many as we won, even winning only three of our fourteen friendlies. Why LFC failed so miserably in their first visit to Division 1 remains a mystery – there was probably no single cause. Media inquests into their many defeats produce some familiar problems – Patrick Gordon missed several good chances against Bolton; sometimes playing with ten men when substitutes were still not allowed; playing better than their opponents, but luck was not on their side – for example, when Everton won 3-0 at Goodison, the Liverpool Mercury judged that ‘the Liverpool team, one and all are to be sincerely congratulated upon the very excellent display they gave’. ‘Persistent ill-luck which attends the Liverpool club, combined with the heavy nature of the turf, was the chief factor in bringing about the disastrous result’ at Pike’s Lane, Bolton. Liverpool’s ‘methodical skill’ was outplayed by Stoke’s ‘dash’. Mercury kept returning to this theme:

A year later, the paper was only slightly more specific, claiming that ‘nothing but a series of mishaps, a severe illness of several members of the team, put the club back into the Second Division a year ago.' In short, there was nothing reported as so fundamentally wrong as to require drastic surgery. The club had been strengthened during the summer of 1894 by the acquisition of John Drummond, Neil Kerr, Bill McCann, Jimmy Ross, to whom Billy Dunlop, David Hannah and John McClean were added during the crisis months.

The opponent for Liverpool’s second test match was Bury, who had finished with a nine-point lead in Division 2. Back to Ewood Park on 27 April 1895, where Bury were unchanged, but Liverpool had five team regulars unavailable through injury, so Robert Neill of Hibs and James Clelland of St Bernard were drafted in (Hearts having refused to assist in this way). It was a desperate tactic, somewhat disparaged by several commentators, including the Edinburgh Evening News: ‘not an expedient suggesting a sportsman-like demeanour, and we should like very much if these temporary transfers were checked.’

It proved to be a disappointing match (‘both sides were bad in front of goal’ ran one syndicated report), culminating in the Bury keeper being sent off for kicking Bradshaw, who was identified by the Liverpool Mercury as ‘the only dangerous man on the Liverpool side’. Athletic News summarised Liverpool’s contribution: ‘the most brilliant of the second-class clubs in 1893-94, they have been the most disappointing of the season that is now almost over. Their repeated failures have been really extraordinary, as they have undoubted talent in their team. They have often collapsed in the most inglorious fashion, and are now doomed to be what may be described as twelve months’ banishment from the society of the leading clubs. It is certainly a crisis in their history.’ The Dundee Courier threw an ambiguous light into the darkness which had now descended on Liverpool. ‘The loss of the big seaport team will be regretted, for the visits to Anfield implied a good haul in.’ Spectators or goals, I wonder.

So, after only one year in the big time, LFC were back in the second division in 1895/96 where their overall exploits from two seasons earlier were repeated. Having won only seven league matches in 1894/95, they now lost only six, sharing the final table at the top with Manchester City. From 14 December 1895 to 3 April inclusive, they scored 57 league goals, conceding only seven against. This time, there was no conjecture about illness, or ill fortune about their opponents - only about what caused dramatic change between losing the Bury test on 27 April 1895 and the start of the new season. So, what happened by the start of the new season on 7 September 1895 which might account for such an improvement?

The first, obvious change is that John McKenna took over the manager’s role from William Edward Barclay on 1 August 1895. Both men had been described as ‘manager/secretary’ since 1892, but now Barclay stepped aside, it is said, to concentrate on the secretaryship of the club, with McKenna now appearing (in the lfchistory.net match summaries at least), as ‘manager’. (It was to be the first step in a long, personal tragedy for Barclay. He gave up the governorship of the Industrial School (an occupation he shared with both his parents and parents-in-law) as well as his functions within LFC before the end of the decade; he lost his wife to mental illness by 1899, which took her to the county Lunatic Asylum, and her death there in 1915; the scattering by marriage of their children, and finally his own suicide in 1917.)

However, the meaning of the word ‘manager’ was not as precise as we later understand it, having a wider, administrative, connotation. Where direction of tactics on the pitch was not coming directly from the top, the role of captain on the day was probably more important than it is today. Team captain during 1894/95 was, first, Andrew Hannah as he had been for every match in the previous two seasons, followed in January by Duncan McLean, with forward Jimmy Ross if the latter was not available. While both full-backs remained on the club’s books, neither played in the new season, and Ross remained in charge on the pitch for the whole of 1895/96, scoring at the rate of one per game. It would appear that captaincy had little or nothing to do with the poor performance during 1894/95.

Before the next season began, a batch of new players was signed – Archie Goldie, Fred Geary, George Allan, John Holmes and Bill Keech, only the last appearing fewer than 19 times in 1895/96. The only midfielder recruited during the season itself was Ben Bull, and he made only one appearance. The main strengthening of the midfield was by pulling Harry Bradshaw back from the front line. The good quality addition between the sticks was Harry Storer, though he arrived only in December.

For the 1895/96 season, the arrangements for deciding on promotion and relegation were reformed, to the general acclaim of reporters. The bottom two clubs in Division 1 and top two in Division 2 played their counterparts in a mini-league, each playing two opposition teams from the other division both home and away, and no longer confined to Saturday afternoons. ‘The present arrangement is both more equitable and satisfactory’, was a typical judgement from the Western Evening Herald. ‘An admirable arrangement’ was the St James’s Gazette assessment, and there is little doubt that it would have lasted well into the twentieth century but for a quirk of fate in 1898 when it was decided to increase the size of Division 1 by two. This had the effect of making the test matches of that year redundant, so the system was abandoned, only revived almost a century later when the money-spinning play-offs were introduced in 1987.

In 1896 LFC was pitted in the test matches against the bottom teams of the First Division, Small Heath and West Bromwich Albion. Even the Birmingham Mail had to confess that the opening game at Anfield, which Liverpool won 4-0, had not gone well. ‘The Small Heath forwards seldom crossed the half-way line, and the Liverpool team did almost as they liked with their visitors.’ There is a long account of the game in the Liverpool Daily Post and (in lfchistory.net) Liverpool Mercury. ‘An easy victory’ according to the Athletic News. ‘The Small Heath forwards ‘were very ineffective……. They never combined well…… Liverpool all round were much the better team. The forwards were speedy and clever, and whilst the passing was well done and to the point, they threw nothing away for want of trying. They were evenly balanced as well….’ The Preston Herald went further in an extraordinary comment, claiming that the referee ‘after the match remarked that the exposition of Small Heath on Saturday was about the worst he had seen from them this season, and warned the Liverpool men not to indulge in too much clever work on the peculiar ground of the Midland club on Monday, but to start in the same determined manner in which they opened the game at Anfield on Saturday.’

The return match at Coventry Road, two days later, was a goalless draw, with Small Heath improving on their earlier game but not to the extent that the Liverpool backs and especially keeper Storer could be beaten. Thus, at the half-way point of the 1896 tests, Liverpool was in a strong position in this mini league. The following Saturday saw another 20,000 crowd at Anfield, where West Bromwich Albion put up a much better fight than their Midlands rival had done. A 2-0 win for Liverpool hides the strong effort by the Brummies, the Athletic’s conclusion being that the result might have been different but for the determination of the Liverpool half-backs to retreat in order to help Goldie and Battles in defence. Lfchistory.net again has a full Mercury account, which eulogises the half back line of McCartney, McQue and the newly acquired Tom Cleghorn.

One more test game to go – the return match at Stoney Lane on 27 April, 1896, where Liverpool lost for the first time in the mini-series. At half time, however, the score from the other match came through, with the surprise news that Small Heath were beating Manchester City (they won 8-0), effectively putting both of the two clubs fighting at Stoney Road into the First Division for the next season whatever their score. The game did nothing to counter the feeling expressed by the Birkenhead News – that the football season was dying a lingering death with nothing of interest to be seen which couldn’t have been played out before the cricket season had begun.

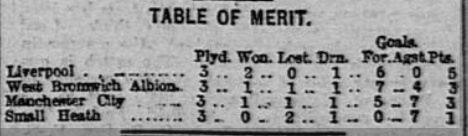

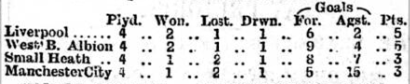

The final table read:

*

Sporting Life reminded readers that, ‘Two years ago, Liverpool had obtained promotion into the first division the league after a very successful record for the second. They failed to uphold their reputation in the higher sphere as many will also recollect, and it is to be hoped that better luck will attend them when they start on the heavier work of the first division next September.’

The Liverpool Mercury assessed correctly that ‘after having figured in the test matches for three successive years, it may be safely assumed that by the experience gained during the past seasons the club will evade that questionable and uncertain ordeal in the future. In any case, it is a certainty that few committees make more strenuous efforts to gather together a class team, and the energetic action by the Anfield executive warrant excellent results in the future.’ A major part of that determination for future reliability was the acquisition of Tom Watson as a new, permanent manager. A native of Newcastle upon Tyne, Watson had taken charge of Sunderland, the first club outside the north-west and midlands to join the Football League. No one has since doubted that it was the skill of Tom Watson (who had twice led Sunderland to the title) which took Liverpool to its first League title in 1900/01. Sunderland, top of the first division in 1892 and 1893, were third from bottom in 1897 without Tom Watson, just surviving the test matches that year.

Tom Watson

This clear evidence that a manager’s influence could be so marked raises once again the issue of whether William Edward Barclay’s competence in guiding football tactics at the top level was at least partly questionable for the yo-yo setback of 1893/96. His transfer of function in the summer of 1895, leaving the successful McKenna in charge on the pitch-side for one season, was, at minimum, a coincidence. Barclay’s involvement in the development of football in the city, both at Everton and Liverpool (he is said to have been responsible for the club adopting its name when a proposed continuation of ‘Everton’ had been rejected by the FA) is undisputed, but his direct experience on the pitch appears to have been limited to having trained boys from the Industrial School (where he was Governor) in the city’s parks.

It is unfortunate that, in those days, there were very few mentions of any manager in match reports in the national press. I’ve looked in vain for any reference to the influence of either Barclay or McKenna, Hannah or Ross on how the games were played. This reticence last until at least the 1920s. When George Kay was appointed in the summer of 1936, the Echo reported that ‘Liverpool FC has never been overstocked in the office or secretarial section, and the directors felt it wise to give Mr George Patterson the single task of secretary, assisted by Mr J Wouse. They decided to appoint a team manager, and that is the newly created post.’ Even then, there was a reluctance to mention the manager’s role, but that could hardly survive Bill Shankly!

Liverpool was one of several clubs which appeared more than once in the test match system; two, indeed (Newton Heath and Notts County) appeared more than Liverpool’s three. Only LFC, however, performed a ‘perfect’ triple yo-yo, being promoted, relegated and promoted in successive years. In more modern times, this has been exceeded by other clubs (such as Fulham, and Manchester City) but Liverpool was the first to do so, a record indeed to forget.

Copyright - Dr Colin D. Rogers for LFChistory.net