LFC assists before the age of film

Note: references to individual games use an abbreviation such as [48:26]. This signifies the 1948/49 season, and the thirty-second competitive match as listed by lfchistory.net.

Identifying and recording those who help to create scoring opportunities for others allows their contribution to be recognised, and working relationships on the field to be analysed. However, the implementation of a good idea is not without its difficulties and controversies. Nowadays, we are used to the name of a player qualifying for an assist being flashed on our TV screens within seconds of a goal being scored; but imagine investigating matches from before the era of film and video. Such a project for lfchistory.net may be unique among the annals of top flight English football – but is it worth doing in view of all the difficulties?

The definition of an assist is a problem. (The word itself was not used regularly for this purpose until the later twentieth century.) It should surely imply intent – if the ‘assist’ was unintended, the result of an accident, should it be recorded? Should the ‘assister’ still be rewarded by recognising his unintended ‘deed’? I wish I could remember the match in which a forward thought he had scored, so he kicked the ball back to the halfway line. The referee disallowed the goal, the linesman having told him that the whole of the ball had not gone over the goal line. So, a defender kicked the ball back, and by chance it bounced into the goal. As the ref had not blown, the ball had still been in play, and the forward would have been credited with an assist for the defender’s goal!

There is no universal definition of an assist, for it does not appear in the rules of the game, each organisation deciding for its own purposes. In England there was no such commonly agreed definition before the late twentieth century. The history of LFC assists must therefore be notionally split into three periods, modern, pre-modern, and pre-video. It is the last which gives the greatest problem, so that, for example, in the 2-2 draw against Notts Forest on 8 January 1949 (48:26), Billy Liddell assisted Fagan to score, but despite the confusion as to who scored Bob Paisley’s late goal (described in the lfchistory.net’s game notes), the assist remains blank. Why is the first included, but not the second?

For any earlier survey, we are almost entirely dependent on the survival of national and provincial newspaper reports, large numbers of which are available online through the British Newspaper Archive, and they often record the players to whom we might give an assist. Even in LFC’s first match, 3 Sep 1892 against Higher Walton, pre-dating our entry to the second division, Tom Wyllie’s part in Jock Smith’s opening goal was recorded. Pre-war reports sometimes follow a pre-set formula which can be very informative, describing the background to a match, away team’s travel arrangements, weather conditions, the match itself with the goals scored, an analysis of at least how the home team played, and suggestions for future tactics. The more experienced reporters vary this plan to suit their individual interest.

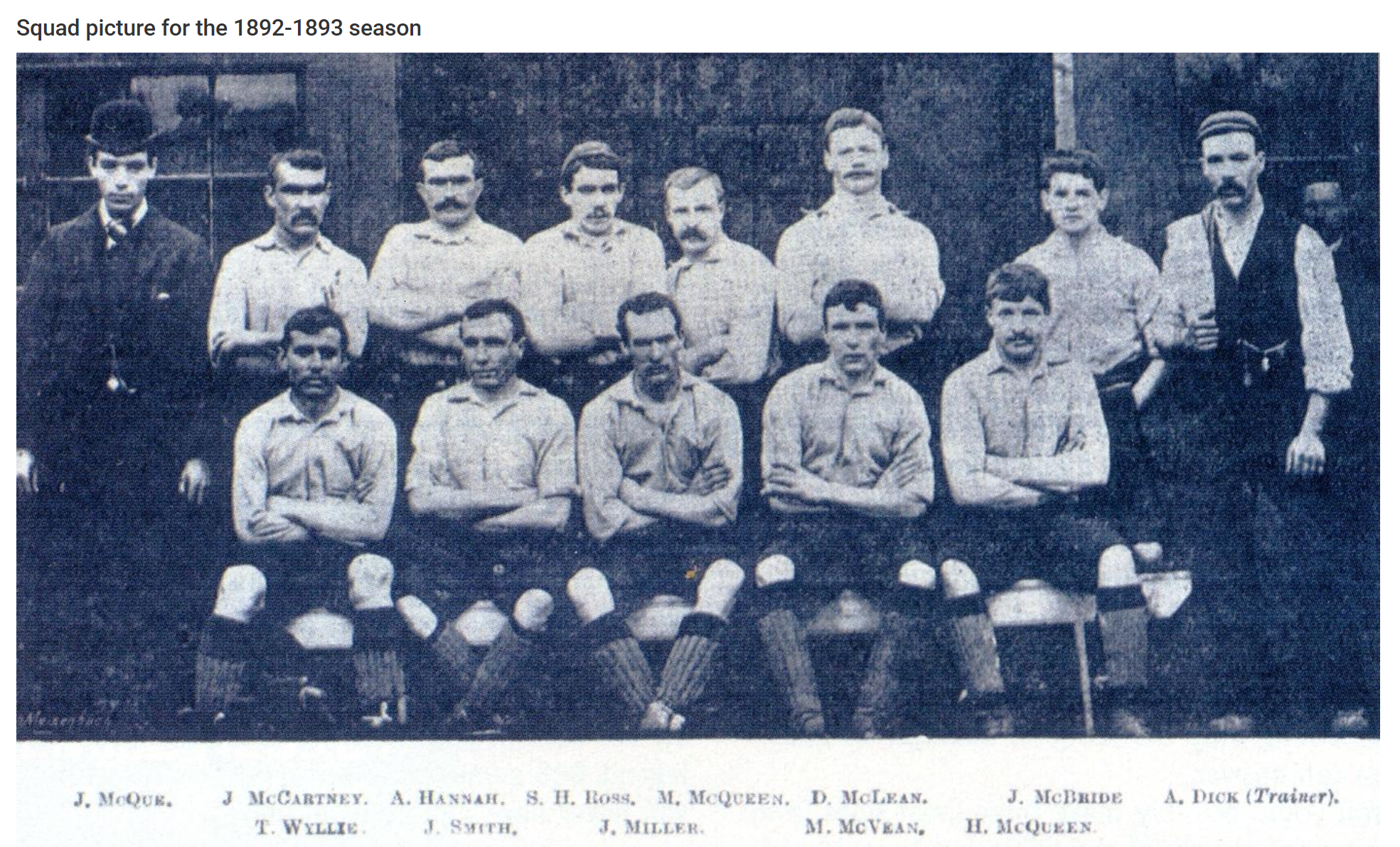

Reading about any same match in, say, both the Liverpool Echo and Manchester Evening News will leave you in no doubt that such reports vary considerably not only in quality, but also by the content coloured by their basic purpose – to sell papers to those who are eager to read about matters of interest to them. It is particularly unfortunate that Manchester’s Football Pink and Guardian are not yet in the archive. Even worse, we assume that whatever is omitted, the facts as reported should be correct, but even that expectation can be unsatisfied. Against Ardwick (93:3) the scorer of the only goal was given as H. McQueen in the Liverpool Mercury, ‘Scott’ (really Jimmy Stott) in Sporting Life, and Joe McQue in Empire News and The Umpire. You can’t even take the majority as the truth, as reports are often syndicated, the same report sometimes appearing in both the Echo and the Daily Post, for example. In the earliest days of the club, I guess journalists can be forgiven for failing to get names right. Echo and Daily Post differ in the game against Arsenal (93/9), the former giving an assist for the first goal to McLean, the latter to McBride. One reporter, evidently baffled by seeing seven Scots in our lineup in the same game, recorded in the Evening News (London) LFC being awarded a free kick when ‘Henderson fouled Macsomebody’. Nor could enquiries be guaranteed a correct answer by asking managers, any more than nowadays. The Athletic reported a conversation with Tom Watson after a Newcastle match (98:27); speaking ‘at 30 knots an hour in his native tongue to his own countrymen, it was difficult to make out what was being said, unless you happened to be an expert in foreign languages’. The reporter on that occasion was that unusual, rarely spotted example, a former professional footballer.

The Team of Macs caused a confusion for reporters

It was not uncommon for papers to differ as to who scored the goals, and the difference between an LFC forward and a defence own goal might depend on the angle from which the reporter was viewing. Against Sunderland [46:19], a Liddell goal in the Echo was changed to an o.g. in a later edition. Goals scored from a scramble (or ‘bully’) in front of goal are notoriously difficult to attribute. ‘How it happened is rather difficult to sum up,’ wrote the Echo reporter describing LFC’s fourth goal against Newcastle (06:34), The Athletic going with a different scorer. So, recognising that, as we all know, you can’t believe everything you read in the papers anyway, how much greater is the problem of having the assists recorded correctly – or even recorded at all? Try taking notes on a full game without a rewind facility, recording at such a level of detail as who assisted each goal. Could you really see such matters during a scrimmage in front of goal, a common reason for the ‘missing’ assist credits? Could you really remember who passed it last to a player fifty yards from goal, or fifty seconds earlier, with no expectation at the time of a resulting goal after a long dribble, or a shot from distance? Analysts will have to decide which paper to trust, when different identities of an assist are published. Johnnie Walker should be credited with an assist for the only goal against Stoke (98:6), but he denied touching the ball because he would have been offside! (See a lengthy account of this story in the following Monday’s Birmingham Daily Gazette.)

The observation of at least one assist was denied by mere accident. Against Portsmouth on 5 November 1938, ‘The match was most notable for one of the most spectacular goals ever seen. And the pity was that the reporter [known as ‘L.E.E.’] had his head down on other business when the first part of Nieuwenhuys’s long run from his own half began.’ (Daily Post 38:13). Birthday boy Nivvy was wearing Balmer’s boots at the time, but that’s another story! There are several other circumstances in which named assists might be unavailable. The most obvious to a researcher is when the goal is scored in last, say, ten minutes of a Saturday match. Bob Paisley’s goal in paragraph three above was on 90 minutes. Papers which appear later in the same day, like the Football Echo, regularly omit detail from the last minutes (or sometimes even the whole second half) because editorial pressure was demanding copy on time. Occasionally even the final score is incorrectly given (e.g. 98:25). This omission was not always updated in any shorter edition on Monday, (Even though phones have been available during the whole of LFC’s history, the Echo carried the emblem ‘By pigeon post and telephone’ for many years.)

Conversely, goals scored in a weekday match are less likely to have their detail recorded than those on a Saturday because of extra publications available on Sunday and Monday which often include such detail. Friday matches are notoriously bad because, by the following day, papers are far more interested in the next matches. Most of the Sunday papers were published in London, so that a match involving a London club is normally much more detailed than one which was entirely provincial, and therefore more likely to include assists.

Another source of exasperation for the assist hunter are games played during a holiday period. Whereas Sunday games started much later (1974), even Christmas Day (to 1964, with LFC’s last Xmas game in 1957), Boxing Day, and the Easter period have had professional football, and these dates often run into trouble with the publication of newspapers.

High-scoring games also seem to be subject to editorial control of the amount of space available for the reports. Some reporters are in any case far more willing to record their opinion of the play rather than what happened. No assists have been published for the Rotherham game (95:26) which Liverpool won 10-1; or for any of the six LFC goals against Newcastle (25:20); or for seven out of eight scored against Burnley (28:22). Another excuse for being less than complete was offered by two reporters for our loss to Stoke on 17 October 1903 (03:8). The Daily Post recorded that our play was so bad that ‘no good purpose could be served by entering in detail upon its main features’; Mercury’s verdict was that ‘in such a game, it is kinder to refrain from individual criticism’.

War and newspaper strikes have been happily among less frequent events which have hindered recording detail of assists. The First World War started an immediate backlash against having any professional football matches, and some papers refused on principle to give anything but the barest details of the 1914/15 season – who played and who scored. The FA allowed grounds to be used for training, with recruitment and aiding the war effort on match days. After the war, typographers based in Liverpool and Manchester went on strike for several months during the 1920/21 season. Liverpool’s first game was against Manchester City, for which there was no Echo, and only one sheet for the Manchester Evening News. Reynold’s News was the only London based publication to carry a report of the match.

As a generalisation, papers seem to be less interested in allocating space for games in the second division - in LFC’s case, 1893/94, 1895/96, and 1904/05, the disdain coming through in one match (05:11) when the Daily Mirror conclusion was, ‘It is impossible to deal anything but briefly with the second class competition.’ Assist statistics for our first season in existence (Lancashire League) are virtually meaningless. Reporting improved during our demoted spell 1954/55 to 1961/62, however.

The 1956 Clean Air Act helped to end an era in which fog simply prevented reporters from seeing the on-field action. The Echo reporter at the Middlesbrough match (30:23) admitted that ‘the scribes had to surmise a lot’ because the fog was so thick. In 1938/39 an FA cup match against Stockport was so spoiled by fog that the Daily Express reported, ‘”Who scored our goals?” was the question Liverpool directors asked themselves after an easy victory….Liverpool won 5-1. And only about half the people knew who had scored……. One of those Merseyside smoke palls came over during the hectic scoring spell in the first half and it was difficult to follow the run of play.’ Assists are unavailable for four of those five goals.

However, the most significant cause of an assist not being credited is a consequence of which definition has been used. In the case of lfchistory.net, it is the teammate whose touch leads directly and in play to the recipient who scored a goal. There would be no assist awarded for scoring from a direct free kick, corner, or throw-in, or if the last player to touch the ball on its way to the scorer had been on the opposing team. (Thus, if the ball rebounded off a teammate’s backside, that would be an assist – off an opponent’s, merely an ass 1st.) A goal scored from a rebound off the goalpost, even from a stray dog on the Highbury turf (22:26), or (very commonly) from an incomplete save by the goalkeeper, would not be allowed. A team mate who allows a pass to go between his legs to someone in a better position to score would not be given an assist; nor would Forshaw when Chambers cried ‘Leave it’ so Chambers could score (25:30); nor would a player who deliberately gets between the opposition and the scorer (Mané protecting Salah from chasing opponents after a long Alisson throw-out, for example).

Compiling lists of assists from papers published in Liverpool, London, the hometown of LFC’s opponents, and more general sporting papers produces relatively disappointing results for Liverpool’s first five decades which suggests that it might not be worth the effort. Only 52 per cent of almost three thousand goals have named assists, which compares unfavourably with those in the 1940s and 1950s, at 62 per cent, and in more modern decades, which have more like seventy per cent. Fourteen per cent were, based on the contemporary descriptions, rejected on assist definition grounds, leaving about one third which remain unattributable because of inadequate reporting.

Meanwhile, we have no assist for Bob Paisley’s late goal at the City Ground, Nottingham in the third paragraph, which runs into some of the difficulties facing identification. It was very late in the match, and more than one other player was involved in the build-up – indeed, the Football Post (Nottingham) gave the assist as Brierley, passing to Done who scored! Even the scorer of the goal had to be identified by the players themselves after the match so it must be chalked up as another newspaper failure.

The most efficient partnerships in Liverpool's history!

It remains to be seen whether an analysis of those who can be newly identified can add significantly to our knowledge and understanding of Liverpool’s earlier history, as LFChistory.net's assist list has done for the modern period.

Copyright - Dr Colin D. Rogers for LFChistory.net