Klopp has been very visible in the centre of Liverpool recently

The end of our 2023/24 season has been overshadowed, yet exhilarated, by having to say ‘farewell’ to our manager. Originally ‘fare thee well’, this is an expression carrying more significance than merely ‘goodbye, cheerio, ta-ta, ‘bye bye, see you later’, etc. (‘Goodbye’ indeed, when pronounced in a certain way, can mean ‘glad to see the back of you’.)

‘Farewell’ means that we look back with fondness and gratitude for our time together, with regret at our parting. It implies also that we hope fate will look kindly on those leaving, bringing success in their future endeavours.

I wondered where Klopp stands in the history of previous managerial exits – how many would have earned and received the accolade of the genuine ‘farewell’ which, without question, we give to Jürgen Klopp for, e.g., the skill, exuberance and joy of a 5-4 over Norwich City, or a 4-0 against Barcelona.

Four managers had to give up the job through ill health - the one-legged, 64 year old Matt McQueen in 1928, George Patterson in 1936, George Kay in 1951, and Gerrard Houllier in 2004. Wishes for their future had to be somewhat tinged with querying how long and active that future would be. Kenny Dalglish’s first resignation, then at the age of only 39, was mainly because he could not stand the mental strain following the Hillsborough disaster, and Klopp himself has cited his struggles to maintain the level of mental input required. So did Bill Shankly. One Liverpool manager, Tom Watson, died still in harness on 6 May 1915.

However, our managers were much more likely to be sacked (or, if you prefer, eased out of the job by mutual consent, and replaced) rather than resign through ill health. Don Welsh, Phil Taylor, Graeme Souness, Roy Evans, Rafa Benitez, Roy Hodgson, and Brendan Rodgers all failed to produce the level of success demanded by the fans, directors, or owners. We have never replaced a manager only because a better man had become available.

Shankly, Paisley, Fagan and Moran retired.

Three others, Ashworth, Dalglish and now Klopp himself, chose to depart in the expectation of taking another job, potentially carrying with them our wishes for future success. The announcement of each of their departures produced a shock in the football world. Table 1 below gives the ages of all managers at the point of their departure from LFC.

Ashworth, a former slipper machinist and football referee, mysteriously left LFC virtually overnight when we were top of Division 1, having won the title the season before at the pinnacle of his career. He failed to succeed with his later clubs. Oldham were relegated to Div 2 at the end of 1922/23, Manchester City at the end of 1925, and Walsall (Div. 3 North) rose slightly to mid-table at the end of 1926/27. Ashworth continued as a manager of Caernarfon and Llanelli, and finally as a scout and football club clerk in Blackpool until the Second World War. He died in Blackpool in 1947, and lies buried in an unmarked grave in Carleton Cemetery.

Dalglish was ‘the only person at Goodison that night [27 Feb 1991] who knew it was my last match’ after five years without European competition caused by Heysel on the day of his predecessor’s departure. He went to second division Blackburn later in 1991, winning promotion in his first season there and the title in 1994/95; but a spell as Newcastle United manager, 1997/98, saw them plunge from second to thirteenth.

Klopp appears to have been the only Liverpool manager who announced his departure early enough for the fans at his last matches to know that he was leaving. It’s natural, at this sad time, to compare Klopp to his predecessors (usually with Shankly because of personality, and dragging the club up from years of underachievement), but difficult because there are so many aspects of the work which influence managers’ standing with the fans. Thanks to lfchistory.net, one factor stands out as being easily available, however – success on the pitch.

The following table gives the bald facts of their percentage wins, draws and losses, together with the number of games on which the percentages are based (which can play a significant part in the percentage figures, the fewer the games the less significant the assessment), plus the average positions at end of each season and at the point of their departure.

The figures are in two batches, before and after 1959 when Liverpool managers began to claim an oversight of recruitment, and the significant increase in the number of games in a season, with Europe and the League Cup then becoming involved.

| manager | %wins | %draws | %losses | #games | position |

age |

| Barclay | 57 | 19 | 24 | 91 | 6.0 | 37 |

| McKenna | 70 | 8 | 22 | 36 | 1 | 40 |

| Watson | 44 | 19 | 37 | 742 | 10 | 56 |

| Ashworth | 51 | 28 | 21 | 142 | 2.5 | 52 |

| McQueen | 41 | 26 | 33 | 229 | 6.8 | 64 |

| Patterson | 37 | 23 | 40 | 384 | 11.3 | 49 |

| Kay | 40 | 26 | 34 | 357* | 10.4 | 59 |

| Welsh | 35 | 25 | 40 | 232 | 12 | 45 |

| Taylor | 51 | 21 | 28 | 150 | 5.5 | 42 |

| Totals | 1,007 (43) | 529 (22) | 819 (35) | 2355 | ||

| manager |

%wins |

%draws | %losses |

#games |

position | age |

| Shankly | 52 | 25 | 23 | 784 | 3.3 | 60 |

| Paisley | 58 | 24 | 18 | 534 | 1.6 | 64 |

| Fagan | 54 | 28 | 18 | 131 | 1.5 | 64 |

| Dalglish (1) | 60.912 | 25 | 14 | 307 | 1.3 | 39 |

| Moran | 40 | 10 | 50 | 10 | 2 | 57 |

| Souness | 41 | 30 | 29 | 157 | 4.75 | 40 |

| Evans | 51 | 25 | 24 | 226 | 4.4 | 49 |

| Evans/Houllier | 39 | 33 | 28 | 18 | 8 | 50 |

| Houllier | 53 | 23 | 24 | 255 | 4.2 | 56 |

| Benitez | 55 | 22 | 23 | 350 | 4.0 | 50 |

| Hodgson | 42 | 29 | 29 | 31 | 12 | 63 |

| Dalglish (2) | 47 | 23 | 30 | 74 | 7.0 | 61 |

| Dalglish (1+2) | 58 | 25 | 17 | 381 | 2.75 | |

| Rodgers | 50 | 25 | 25 | 166 | 6.25 | 42 |

| Klopp | 60.896 | 22 | 17 | 491 | 3.6 | 56 |

* Also games in 1939/40.

Position = Final positions In Div 1 or 2.

The total number of matches since 1892, excluding those with a caretaker manager, is 6,121. We thus have a crude expectation, derived from our history of long term proportions of wins, draws and losses, with which to compare the pitch performances of past and future managers:

In 1893 to 1959, we had 46% wins, 21% draws and 33% losses.

In 1960 to 2024, we have had 54% wins, 24% draws, and 22% losses.

So, the ‘Klopp out’ idiots of 2015 have their way at last. What sort of things can the above table show us about the comparable record of Liverpool’s 20 managers since 1892? See what you can spot - for example:

Only three men (Watson, Shankly and Paisley) have managed more Liverpool games than Klopp has.

With a few exceptions, pre-war managers did not fare nearly as well as those later, only three winning more than half of their matches. Yet the latter have encountered more difficult opposition, especially during the Premier League history.

Dalglish retains his crown as ‘King Kenny’, from the memory of the 7-0 demolition of Spurs (2 Sept 1978), to the contrasting faces of Dalglish and Ferguson during LFC’s 0-5 demolition of Manchester United at Old Trafford (24 Oct 2021) – the man to whom we have never really said farewell, as he has never really left us. His average league position is higher than Klopp’s, even when his poorer second spell is included, but Klopp comes within a whisker of Dalglish’s win/draw/loss percentages on the pitch, and (by this measure) clearly better than the record of Shankly or Paisley.

Houllier’s record was only marginally better than that of Roy Evans.

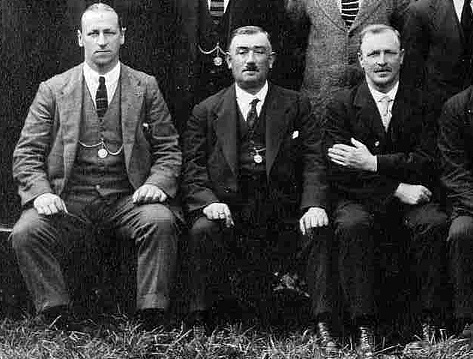

George Patterson, David Ashworth and Matt McQueen

So back to farewell. There is a paradox about wishing a former manager well if he might subsequently bring an opponent to Anfield, and we really should not wish Klopp any more success than his predecessors have enjoyed. The five managers whose willing or unwilling departure from Liverpool at a young enough age to take a new job cannot be said to have ‘fared well’ when bringing a new club against Liverpool, with or without vengeance in mind.

Ashworth won 1 drew 0, lost 2

Dalglish won 4 drew 0, lost 6

Benitez won 0, drew 2, lost 5

Hodgson won 2, drew 0, lost 11

Rodgers won 2, drew 1, lost 5

Total won 9 drew 3, lost 31

I do not believe that the 26 January announcement of Klopp’s departure was the main cause of the disappointing end to the season, though it was clearly connected. We won ten of the next twelve matches, which continued the remarkable season he was having, an even better result than the previous thirty-three games thus far in 2023/24. It has often been noted that the decline, following the MUFC result on 17 March, has corresponded to that of Emma Hayes’ Chelsea women in their last few games, and needs a much deeper piece of research to understand the true causes.

Klopp has said he will not manage another English club. One day, he will be in the running for his national team. Surely Germany, of all countries, would not appoint a manager who cannot watch penalties – would they? They’d have to turn a doubter into a believer.