Liverpool FC carries the shame of two disasters which, even in hindsight, have been largely attributed to the misbehavior of some of their own fans.

The first, in a 1968 FA Cup draw at Walsall, included some comparatively minor vandalism, damage to some stand barriers, a downward crush of spectators and a ‘mass of bodies’ being treated for injuries on the pitch. It was an escalation of football hooliganism which had become all too common in England during the 1960s. I’ve been unable to find any prosecutions arising from this event (here is a link to the the Guardian's press report).

(By an extraordinary coincidence, sixteen years later (14 Feb 1984), also at Walsall, a wall from the corner flag to the posts, recently modernized, collapsed at Fellows Park when LFC fans pushed forward to celebrate a goal by (either Ian Rush or Ronnie Whelan, two different reporters!) Seventeen were injured. Reference back to the 1968 episode was not noted in any of five reports on the match.)

The second, at the 29 May 1985 European Cup Final against Juventus at Heysel in Belgium, was far more serious and far more consequential, a turning point in the way football in England has been organised. Here, some supporters allowed the importance of the occasion, on foreign soil away from home, to persuade them to engage in ferocious confrontation with opposing fans, culminating in 39 deaths: thirty-two Italians (including two children), four Belgians, and two French. Some six hundred others were injured. A doubly unfortunate 39th victim was Patrick Radcliffe, an Irish historian who was not even a football fan – he was working for the Brussels archives. and had attended the event to accompany a friend. Alas, a Northern Ireland coroner had no authority to investigate his death, even if he had been repatriated to Belfast.

Pictures of the scene are reminiscent of medieval depictions of hell.

Heysel was a culmination of increasingly riotous behaviour by football fans across Europe Descriptions of the disaster can be found in players’ autobiographies as well as contemporary reports and film. Some players, including Phil Neal (our captain for the match) could not bear to talk about the experience. This article, however, concerns its aftermath.

*

The apportionment of blame was rapid, not only because the status of the match itself had naturally generated. The organizing body, UEFA, had an observer there, whose reaction next day was, ‘Only the English fans were responsible. Of that there is no doubt.’ The report of a Belgian judge came out over a year later. She had considered whether local officials, the stadium owners, the police, or UEFA itself should carry part of the blame, but in the end concluded that only the Liverpool fans were responsible.

That is not to say that there were no extenuating circumstances, which certainly made the disaster worse than it might otherwise have been. There had been trouble in Rome the year before – LFC fans had been attacked in the street after their Champions League final victory on penalties. Some Liverpool sources claim that the predicted retaliation at Heysel was triggered by missiles from the adjoining section for Juventus fans. UEFA does not seem to have been careful enough in allowing the inexperienced Belgian authorities to organise the event. It would not be the first time that governing bodies had made an overriding political judgement on a footballing issue, Heysel being the national stadium in Brussels when much better locations were available. (The stadium, already condemned before the disaster, was rebuilt ten years later.) The choice of venue for the match had led to criticism from both Liverpool and Juventus because of the dilapidated state of the stadium. Even before the match started, clubs and players had expressed strong concerns about the inadequate policing and the flimsy (‘chicken-wire’) separation of English and Italian fans. Ticketing arrangements were also defective. One witness reported walking into the press box unchecked.

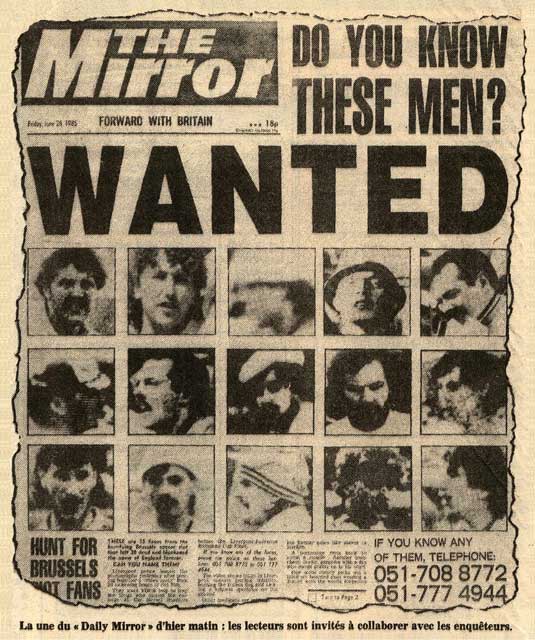

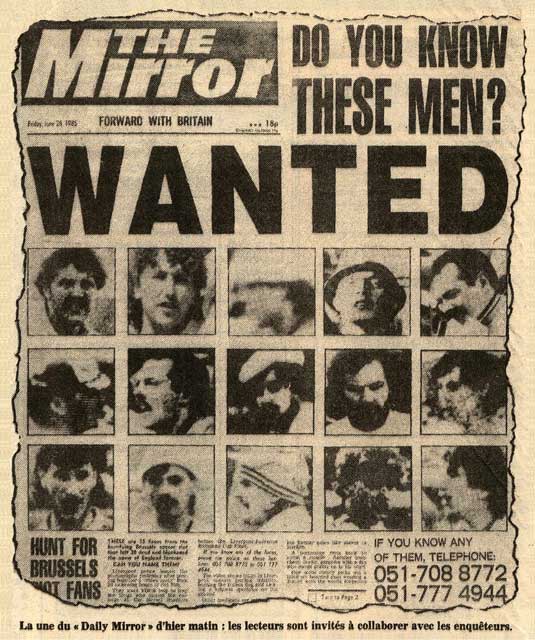

The trouble with extenuating circumstances is that, by providing the circumstances around the actions, they tend to diminish the guilt of the perpetrators. These factors were taken into account during the trial and appeals; thirty-four Liverpool fans were arrested, twenty-six faced manslaughter charges, and almost four years after the event, fourteen fans from England were given six-year sentences (three in practice) for involuntary manslaughter, with a £2,000 fine. (The remainder were acquitted.) Investigations had been greatly assisted by the actions of the British police and even a fire brigade was involved. Local officials were also put on trial. A senior police officer was given a nine-month suspended sentence for ‘grave omissions of duty’; the ex-chairman of Belgium’s Soccer Federation received a six-month sentence, also suspended. Five other officials, including the Mayor of Brussels were acquitted.

Aspersions have been cast on whether those in red were true Liverpool fans or merely hooligans bent on enjoying another rampage. Indeed, some of those arrested had similar records back home. There was clearly an element of misguided ‘defending the honour’ of Liverpool FC if it was perceived to be under threat or insult; those who bring the club into disrepute can hardly call themselves ‘true fans’.

The reputation of English fans was not high, even preceding the Heysel disaster, and four years later the immediate public reaction to Hillsborough almost symbolized the antipathy felt between the city of Liverpool and the Tory government. National and local officials, police and right-wing press all jumped on an anti-Liverpool bandwagon which Walsall and especially Heysel had set rolling, without learning the lessons of the investigations in Brussels.

*

One of the earliest consequences of Heysel was Liverpool’s loss of our precious commodity, Ian Rush, who was sold in order to reduce the predicted loss of revenue following the ban. Many European clubs had wanted him - Terry Venables’ Barcelona, for example – but ironically he went to Juventus of all clubs following their reassurance that the Italians laid no blame for Heysel on the English players – only on the LFC fans. Rush reported that his experiences in Turin confirmed their advice.

The ban from entering European competitions for all clubs in England imposed by FIFA and UEFA following Heysel, was initially five years, with Liverpool FC being banned indefinitely, later changed to seven years, and finally six. Its anticipated financial loss hit Liverpool FC much harder than any other club. In the season which ended with Heysel, we were second in Division 1, and alternated between first and second during the next six seasons. The ban also prevented Everton (twice) and Arsenal a place in the European Cup. Liverpool, Everton, MUFC, Coventry City and Wimbledon missed out on the European Cup Winners’ Cup, and nineteen English clubs were denied entry to the UEFA Cup. Even into the 1990s, UEFA’s points system for seeding, based on a club’s performance in European matches in the previous five years, worked against the English teams.

Football historian Rogan Taylor has identified this loss of revenue as one of the contributing factors in the development of the English Premier League in 1992.

*

Liverpool was not totally cut off from European football during this period. Friendlies were allowed, though not in Belgium for any English club. Probably by mutual consent, there were friendly games against only English teams during the 1985/86 season, but by the summer of 1986/87 a number of continental European clubs agreed to play friendly matches against Liverpool Their willingness to participate was first shown by clubs in Denmark and Sweden, then Hamburg SV and Real Sociedad. Vålerenga in Norway, Osasuna in Spain and Atletico Madrid joined in the following year, with Finland and Ukraine in 1989/90. As early as 2 August 1990, the first Italian club, Fiorentina, welcomed us back to their Massa stadium, but that was part of the deal for Glenn Hysen’s transfer to Liverpool. We had to wait till 2005 before we were drawn against Juventus once more.

*

In England, the power of the courts to ban fans from grounds was included in the Public Order Act, 1986, a piece of legislation covering many offences, including riot, harassment, and abuse on grounds of race, etc.

The Football Spectators Act 1989 allowed convicted hooligans to be banned from international matches. (The Football (Disorder) Act 1999 made this a duty on the courts, and was extended to home matches by the Football Disorder Act of 2000.)

The Football Offences Act 1991 specified individual offences during games – throwing missiles, racist chanting, and pitch invasion, etc). A private member’s bill for an insertion to the 1991 Act is currently at the Committee stage in Parliament, making unauthorised presence at a football match a criminal offence.

The Football Spectators (Seating) Order 1994 was directed particularly at the top two tiers of football, putting into effect recommendations of the Taylor Report into the Hillsborough disaster, and giving authority over ground regulations and implementation to the Sports Ground Safety Authority. Since stadiums became all-seater, the sort of riotous behaviour between fans seen at Heysel has normally been outside a stadium. Inside or out, there is an army of camera-toting fans eager to record anything unusual which might bring the club into disrepute. However, it is clear from a lunchtime Black Country derby on 28 January this year (2024) that it can break out again despite all the legislation against it.

*

I would argue that the main thread of antagonism between fans was not between Liverpool and Juventus, but rather between Liverpool and Roma. As noted earlier, there had been trouble after the European final between them on 30 May 1984, the first encounter between the two clubs, a match which the Italian fans had been confident of winning. (See Chris Wood’s article ‘Great matches: Liverpool beat Roma at their own ground’, LFChistory 6 Feb 2006). Retaliation by Liverpool fans has been seen as a significant part of the explanation of what happened at Heysel, and 1985 was another in a long feud between the Italian capital and visiting fans from other European cities, including others from England, Spurs having felt the brunt of it in 2012.

Liverpool visited Roma on 15 February, 2001 in a UEFA Cup tie when LFC fans suffered stabbings, assaults with chains, and a barrage of missiles (bottles, bricks etc) both in and out of the stadium. We were by no means the only visiting fans (and not just from England) to suffer a similar fate as Italy failed to rein in the ultras.

An additional factor in the 24 April 2018 Champions League semi-final against Roma at Anfield was our recent purchase of Mo Salah from that very club in the previous summer window. He rubbed salt into their wounds by scoring the first two in the 5-2 victory, having already become a bright star in the Liverpool firmament. Even before kick-off, however, some ‘ultra’ Roma fans had been on the rampage in the streets, the main casualty being Irish FC fan Sean Cox who was given life-changing injuries. The violence was Klopp’s ‘ugly face’ of football.

Once again, the perpetrators were declared to be ‘not true fans’. However, the Roma club acknowledged responsibility for their own fans’ behaviour by giving a generous donation towards Sean’s rehabilitation, and at the second leg in Rome, their team wore T-shirts with ‘Forza Sean’ (‘Stay strong, Sean’) emblazoned. Italian police guaranteed LFC fans’ safety by issuing good advice in advance, and putting 1,200 officers on duty.

*

Before the Champions League final against Real Madrid in 2022, Paris police sprayed Liverpool fans with pepper and tear gas. ‘Blame the fans’ was alive and well. The chaotic crush at the Stade de France was seen around the world, as the Liverpool supporters suffered another crisis through the eyes and memories of Hillsborough. When kick-off time arrived, the Liverpool end was still ‘sparsely populated’. Once again, the old association of Liverpool and disorderly conduct determined the immediate, self-defending reaction from UEFA, police and politicians. The fans, accused of trying to enter, en masse, many without tickets, were the easy target. (Fake tickets had indeed been sold on the internet.)

The later investigation into the event laid the blame squarely on the organisers and the police. UEFA’s commissioned independent report, published on 13 February 2023, found that UEFA’s own failings had been responsible for putting LFC fans through another trauma.

*

One day, LFC will face Italian clubs again, and the memories of Heysel will surface, for their fans will be unable or unwilling to forget Heysel, any more than we could forget Hillsborough. If such an outcome were to be caused by LFC fans in future, I would make a plea to improve on the well-meaning reaction such as the ‘amicizia’ (friendship) displayed across the Kop in 2005 (even though it was after consultation with Juventus) as it does not convey anything of the responsibility for the disaster which we, as a collective body of fans, should bear. Many in the away end turned their backs on the sign. However, if we choose to show the Italians that we do regret that it happened by using such phrase as ‘Chiedo perdono’ (I ask for forgiveness), I believe that this would mean a lot more and, truly reflect how the great majority of LFC supporters actually feel.

Our main memorial to Heysel at Anfield is a plaque on the outside of what was the Centenary Stand (now the Sir Kenny Dalglish stand) for the public to see. There is also a small memorial plaque dedicated to the victims inside Liverpool's club museum, with the shirt worn by Kenny Dalglish on the fateful night draped alongside. St John’s Gardens in the city bears a ground-based plaque placed by the city council in 2010 when the new Mayor, Joe Anderson, planted a memorial tree marking the 25th anniversary.

It's the fortieth anniversary of Heysel next year. How should we mourn a disaster from a world we have hopefully lost? We are surely big enough to show our collective shame, not try to hide or forget it as we (and even Juventus) seemed to do for fifteen years after the event. Meanwhile, we might face Roma in the Europe League later this season – now that would be a mark of how far we have left the past behind us.

Article by Dr. Colin Rogers for LFChistory.net

Other articles by Dr. Rogers