Robbie Fowler, having joined LFC on the ground staff as a teenager, turned professional on 9 April 1992, and then entered a seventeen-month, frustrating period, scoring for the reserves, but having to look at the next seventy-two team sheets in his ‘agonizing wait’ to see if he had finally been selected for a first-team debut. Even then, it was only in a League Cup game at second division Fulham, and he was still only eighteen. He scored, of course – you can watch it on lfchistory.net.

How common has that experience been for uncapped players at Anfield? He was certainly in good company. Tommy Smith, another ground staff boy at 15, was not the only one having to go nervously to the toilet (as he later confessed) before yet another team sheet went up without his name. Most, of course, never make it at all, the plight of the younger ones being highlighted recently by Alexander-Arnold’s proposal for a national ‘After Academy’ to target the great majority of hopefuls who will fail to make the grade by the age of 16. Even the few who are given a professional contract with the club are not guaranteed progression to the top level – some with well-known names like Jim Magilton, or Peter Gulacsi failed to make it. Another 15-year-old, Roy Evans, joined the club as far back as 1963, became a professional in 1965, and then waited an astonishing 249 games before his debut on 16 March 1970 – and then it was only because Geoff Strong was injured. They also serve who only sit and watch.

An additional frustration for a debutant-in-waiting must be hearing the knowledgeable Anfield crowd calling for his first appearance long before the manager decides it is his time. Raheem Sterling was one such during a 111-match wait for his first call up.

What has been the normal Liverpool experience of those who were finally selected? How long have they had to wait between signing a professional contract and their first team debut? In trying to answer that question, we need to have a meaningful basis for calculating the time gap. Vladimir Smicer joined LFC on 24 May 1999, Didi Hamann two months later, and both made their debuts on 7 August, seventy-five days and sixteen days respectively later. However, neither could have had his debut any earlier, because there were no fixtures – 7 August was the first after they had joined. For the purpose of this article, therefore, I have taken the length of their wait as zero – in other words, they did not have to watch from the stands as their new colleagues played a single match without them. Having been recruited at that time of year, of course, they have a better chance of playing in the first available match, having a pre-season to show off their skill.

The results are based on 440 players whose dates of signing for LFC are known, or who joined after the last match of one season but before the first of the next season. They vary from the zeros of Smicer and Hamann to some hundreds of games. Tiny Bradshaw had his debut on the day he joined Liverpool. (I was tempted to score him as a minus 1.) Tommy Smith’s wait was 51 games after turning professional, while Tommy Lawrence went through two managers (Taylor and Shankly) in his 227-fixture game of patience, since surpassed by Danny Ward on 228!

Goalkeepers, indeed, are in danger of having the most frustrating time of all the positions on the pitch. The unluckiest were Ward and Lawrence, but John Ogston (91, a Shankly recruit), Patrice Luzi (85, Houllier), Ray Clemence (71, Shankly), and Diego Cavalieri (67, Benitez) each had the equivalent of more than one season’s fixtures on the sidelines. Off the pitch, their lack of luck continued, as so many never get a game, including eight of the eleven goalkeepers recruited by Jurgen Klopp!

However, ten of the thirty-two goalies joining Liverpool since the second world war were selected immediately, and a further eight watched matches numbered only in single figures before their debut.

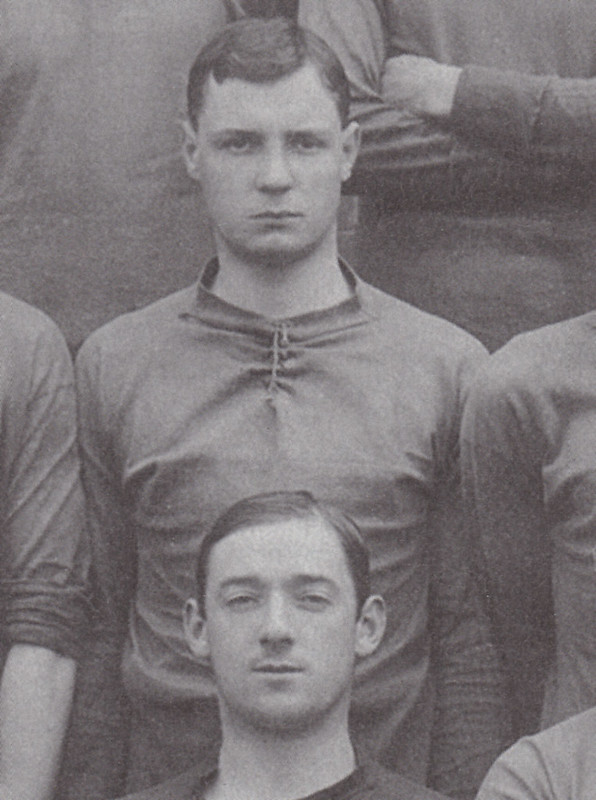

Keeper Augustus Beeby had to wait patiently for his chance

No LFC goalkeeper before the Second World War suffered such an indignity as the above examples, the average wait (1893/94 to 1939/49) being 14.5 matches. Unluckiest was Augustus Beeby, who waited 40 games before his first team debut. (In 1892/93, almost everyone was selected for the first match after they signed for LFC.) Even that great keeper Elisha Scott could not get a first team place until the 22nd time of asking.

Some never made it. There was no ‘bench’ until substitutes were allowed in 1965/66. Thereafter, there have been twenty-six goalkeepers (twenty during the Premier League era) who have failed to crash through the a ‘glass-ceiling’ above the bench, and did not have not a single appearance for Liverpool in a match.

The problem for new goalies has been the skill, longevity and comparative freedom from injury enjoyed by many first choice keepers, especially Elisha Scott himself (1913-1934), Arthur Riley (1925-1940), ironically Tommy Lawrence (1959-1971), Ray Clemence (1967-1981), Bruce Grobbelaar (1981-1994), and Pepe Reina (2005-2013).

*

Nineteen players had their immediate debut during the 1892/93 season, only goalie Billy McOwen having to wait before his on 15 April. By LFC’s second season, goalkeeper John Whitehead had watched 37 games before his first appearance, but five of the other fifteen newcomers did not have to wait, except Billy Dunlop (20). That pattern – only a minority of new players taking to the field immediately after they joined - continued until the Second World War, with the occasional outfield player having to wait a surprisingly long time – Samuel Hignett, for example, watched 149 games from the stands in 1903 to 1907. On the other hand, goalie Ned Doig had no competition for his place in 1904/05. Least fortunate of the outfielders before World War One was the ‘not very effective’ William Stuart who watched LFC for well over a year before being handed his debut.

The average wait for 145 players (before the First World War but excluding 1892/93) was 9 matches before their debut on the tenth. Between the wars, calculating on the same basis as above, an average of fourteen matches were watched by 142 hopeful players before their debut, eleven being the final figure for both periods added together before the Second World War.

*

There is little point in trying to distinguish the practice and effectiveness of different managers in this respect until the arrival of Bill Shankly at the end of 1959, because recruitment and team selection were formerly undertaken by the club’s Board of Directors. It becomes meaningful to subdivide the later period into the reigns of each manager in order to see if there was any major difference between how the waiting time was handled, and how far each manager was astute (or desperate) enough to avoid having players waiting frustrated in the wings.

Col 1 = manager

Col 2 = start date

Col 3 = number of players recruited (number whose wait length for debut is known)

Col 4 = number with no debut

Col 5 = number waited under 10 games (played next possible match)

Col 6 = number waited 10 or more

Col 7 = longest wait for debut (some Rodgers/Klopp still wait)

| Manager | Start | Number | No | 1-9 | 10 plus | Longest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shankly | 1/12/59 | 54(39) | 3 | 19(7) | 20 | Roy Evans 249 |

| Paisley | 26/7/74 | 27(20) | 5 | 8(6) | 12 | Gary Ablett 199 |

| Fagan | 1/7/83 | 10(8) | 2 | 5(2) | 3 | Alex Watson 157 |

| Dalglish | 30/5/85 | 33(29) | 4 | 13(10) | 16 | Don Hutchison 133 |

| Moran | 22/2/91 | 0 | ||||

| Souness | 15/4/91 | 17(15) | 1 | 13(9) | 2 | Lee Jones 127 |

| Evans | 31/1/94 | 32(19) | 12 | 10(5) | 9 | Stephen Warnock 281 |

| RE+GH | 16/7/98 | 1(1) | 0 | 1(1) | 0 | Vegard Heggem 0 |

| Houllier | 12/11/98 | 46(36) | 2 | 26(15) | 10 | Mark Smyth 138 |

| Benitez | 16/6/04 | 73(51) | 7 | 34(16) | 17 | David Amoo 170 |

| Hodgson | 1/7/10 | 17(9) | 4 | 7(3) | 2 | Suso 107 |

| Dalglish | 8/1/11 | 16(11) | 2 | 7(5) | 4 | Danny Ward 228 |

| Rodgers | 1/6/12 | 47(33) | 4 | 29(18) | 4 | Sergei Canos 162 |

| Klopp | 8/10/15 | 57(37) | 9 | 27(14) | 10 | Tony Gallacher 102 |

The managers who showed the most confidence that their new players were worth putting onto the team sheet immediately were Graeme Souness (only three of whose appointees waited more than one match), and Roy Hodgson. Bill Shankly was the most cautious about doing so. (Klopp is far more likely than Shankly to bring on his new players early in their LFC career, but then we are playing many more games during this modern era, and the extraordinary match against Aston Villa on 17 Dec 2019 was the occasion to give eight young players their debuts.)

Of the 112 players who were chosen for the first game available after joining, most were in their 20s; youngest was Joe Gomez (18 when he played against Stoke City on the first day of the 2015/16 season); Joe Fagan gave Barry Venison’s his 22nd birthday present to coincide with his first-game debut. Keeper Paul Jones was the oldest at 36, but the oldest outfield player, at 35, was Gary McAllister.

(That pattern shows little difference to the equivalent list from 1893/4 to 1938/39, during which the youngest debutant was 18-year-old James Hughes, the oldest was keeper Ned Doig at 37 (remaining with LFC for another four seasons), and the oldest outfield player was ex-Evertonian Edgar Chadwick aged 33.)

*

The majority of these long waits appear to have been justifiable on skill levels alone. They may have been good enough players (‘promising’ the word often used at that stage in their career) but not yet better than those tried and tested whom they were trying to replace. However, the popular Stephen Warnock had the longest wait by players listed in col. 6, suffering three broken legs and a loan spell before realising his ambition with his debut five years after turning professional with Liverpool. Suso was still very young when Hodgson and Dalglish failed to use him, and by the time Brendan Rodgers reversed that decision, Coutinho had appeared on the scene.

*

The interpretation of col. 5 is not straightforward, but we can have a guess at those who were plunged in at the deep end by the managers who had appointed them. I suspect that the main (or only) position for which a panic buy had been made was goalkeeper – otherwise it would seem that a recruit being played in the next available match had given the manager a considerable degree of confidence in his ability on the ball and into that team. We thus have a possible measure of the manager’s recruitment skill by looking at how far that player repaid the club by performance levels which justified long-term his original selection into the team. (Signings by Jurgen Klopp have been too recent to make a judgment on the same basis.)

Head and shoulders above their successors were Shankly and Paisley, whose 13 immediate debutants went on to play for Liverpool three thousand, nine hundred and fifteen times. The ability of these two managers to appoint players who were both skillful and loyal was quite extraordinary. At the other end of the scale, Roy Hodgson’s three most promising appointees (Jovanovic, Meireles and Konchelsky) made only eighty appearances.

*Robbie Fowler ‘My autobiography’ (2005, p. 63)

Article by Dr. Colin Rogers for LFChistory.net