In 1955/56 Everton were on a high – they’d just escaped from Division 2, changing places with a descending Liverpool, who remained there until the end of 1961/62. Meanwhile, at Goodison, rising to the safety of 14th in Division 1, they were already seeing changes in the top flight which they were determined to follow.

There had been pioneers of floodlighting in the English game long before that (notably Herbert Chapman at Arsenal), but the FA had not allowed artificial lights to be used except for friendly matches until the early 1950s when they bowed to professional, public and financial pressure. The result was predictable – clubs which so far had resisted installing lighting now had to catch up with the others. By 1959, even our nemesis Worcester City was floodlit.

Ironically, the development spread more quickly in the south of England where the sun sets a fraction later than in the north. In that same year (1955/56), they even established a Cup knockout competition, separate from the FA league and Cup, which comprised Aldershot, Brentford, Crystal Palace, Millwall, Orient, Portsmouth, QPR, Reading, Watford, and West Ham United. Arsenal, Chelsea, Charlton and Luton joined in 1956/57. This Southern Professional Floodlit Cup ran for five seasons, after which the League Cup overtook it.

Meanwhile, on Merseyside, we were subject to the same old, awkward timing of when games were due to start to allow for the maximum number of fans to see the whole match at a time when Saturday morning at work remained the norm. For much of the year, the traditional 3:00 pm start could be maintained only between mid-February to mid-October.

During late October to early December, the 3:00 kick-off was brought a quarter of an hour earlier until the earliest at 2:15. (A bank holiday might even start late morning.) Even then, although Merseyside being on the west coast helped a little, an Anfield sunset was hidden by the Kop anyway, and we all know how cloud cover diminishes the amount of light available during winter months. The effect of starting as early as 2:15 on gates, even on a Saturday, is almost impossible to measure. There were so few of them (two, three or four a season) and the size of the crowd depended on the lottery of the exact dates and opponent concerned. On 1 December 1957 Sheffield United attracted 34,159 to Anfield; three weeks later, only 18,754 watched the game against Bury, the absentees presumably on shopping duty. A game on Boxing Day could double the gate.

The 2:15 starts lasted a surprisingly short time, and there were seasons when 2:30 was restored even in late December. 3:00 starts returned as early as 3 February in 1951/52.

For these reasons, it would be fair to conclude that the urge to establish floodlit football had relatively little to do with the inconvenience of changing kick-off times to suit the daylight hours available. It was a good excuse. The real pressures came from novelty and convenience for fans, but more than anything from the perceived financial benefits from having larger crowds. It had nothing to do with competitive European matches which started in 1960, with Liverpool entering in 1964/65.

The financial drive to get Merseyside floodlit appears to have been stronger at Goodison, where there had been experiments (sometimes with a white ball) decades earlier, rather than Anfield after 1892. Both clubs had approached the subject with caution, waiting to see if lights at other clubs were just an expensive white elephant. Everton’s directors are known to have visited southern clubs early in the 1950s to learn the lessons – they went to Watford early in 1954 for example. A sub-committee was established to work out the details and two years later the installation of pylons at Goodison was commissioned.

Meanwhile LFC’s directors had put out tenders for lighting at Anfield during the 1955/56 season, and had obtained an estimate of £33,000, too great a sum for the club when ‘improving playing resources’ was deemed to be more urgent. They regarded the purpose of floodlighting as the improvement of gates, especially in the middle of winter, as a result of standardising kick-off times.

Anfield lit during the Liverpool Senior Cup

Shareholders at the next AGM (July 1957) expressed great interest in the development, probably with the fear that the cost of the floodlights might have a bad effect on the club’s ability to spend on new players. This view was against a background of a financial loss made by the club in the recent season. However, Director Harold Cartwright reported that,’What six months ago was only a dream is now becoming a reality.’ Some lights had been installed to good effect at the training ground, and there were changes for the Anfield lights designed to reduce the cost.

Director Richard Martindale reiterated the optimism of the previous meeting, saying that the club hoped to increase revenue by being able to start all Saturday matches by mid-afternoon, even during the winter months. That increased revenue to cover the cost of lighting would not come from any increase in the entrance fee to matches. The Chairman (Mr T.V. Williams) would not divulge the actual cost, but announced that some Directors had ‘guaranteed the required amount’ if that projected increased revenue was insufficient. There was no named involvement of John Moores in the minutes. The effect of the new lighting facility at Anfield was immediate. Their last league match earlier than 3:00 was against Bristol Rovers on 26 October 1957, four days before they were switched on. Every match thereafter started at 3:15 or later, though there were two FA Cup games on 4 and 25 January which kicked off at 2:15 and 2:45. They even started the Rotherham game in November at 7:00 pm. The 3:15 starts remained the norm until 1961/62 – then the ‘traditional’ 3:00 was reinstated, lasting until TV entered the fray in such a dominant fashion.

If increasing revenue was the main factor in erecting the Anfield floodlights, there were disappointments for LFC. The total number of matches at Anfield did not rise - nor could they, unless the number of (normally low-gated) friendlies or FA Cup matches increased, which they did not. Home gates during December remained erratic, responding to factors other than lighting.

Did the gates increase generally because of evening matches, plus the likelihood of 3:00 starts being

able to finish with the new lighting on? The average league gates while we remained in Division 2 were

as follows:

1954/55: 36,230

1955/56: 37,228

1956/57: 35,793

1957/58 until floodlights 38,469

1957/58 with floodlights 38,478

1958/59: 36,653

1959/60: 31,416

1960/61: 29,607

In other words, there was an understandable spike in interest during the first season (though that was clear even before they were switched on), but it did not last. Nor did the new lights have much effect on the addition of weekday normal friendly games. Hibs (who had their own floodlights by 1955 and who fielded Jimmy Harrower whom we signed a few weeks later; we’d had Younger from them already) was welcomed by almost 20,000 at 7.00 pm on 13 November 1957, but thereafter no non-cup friendly was held at a floodlit Anfield on a weekday for at least the next twenty years. Both Shankly (who had arrived from a Huddersfield Town with no floodlights in 1959) and Paisley discouraged friendlies at Anfield.

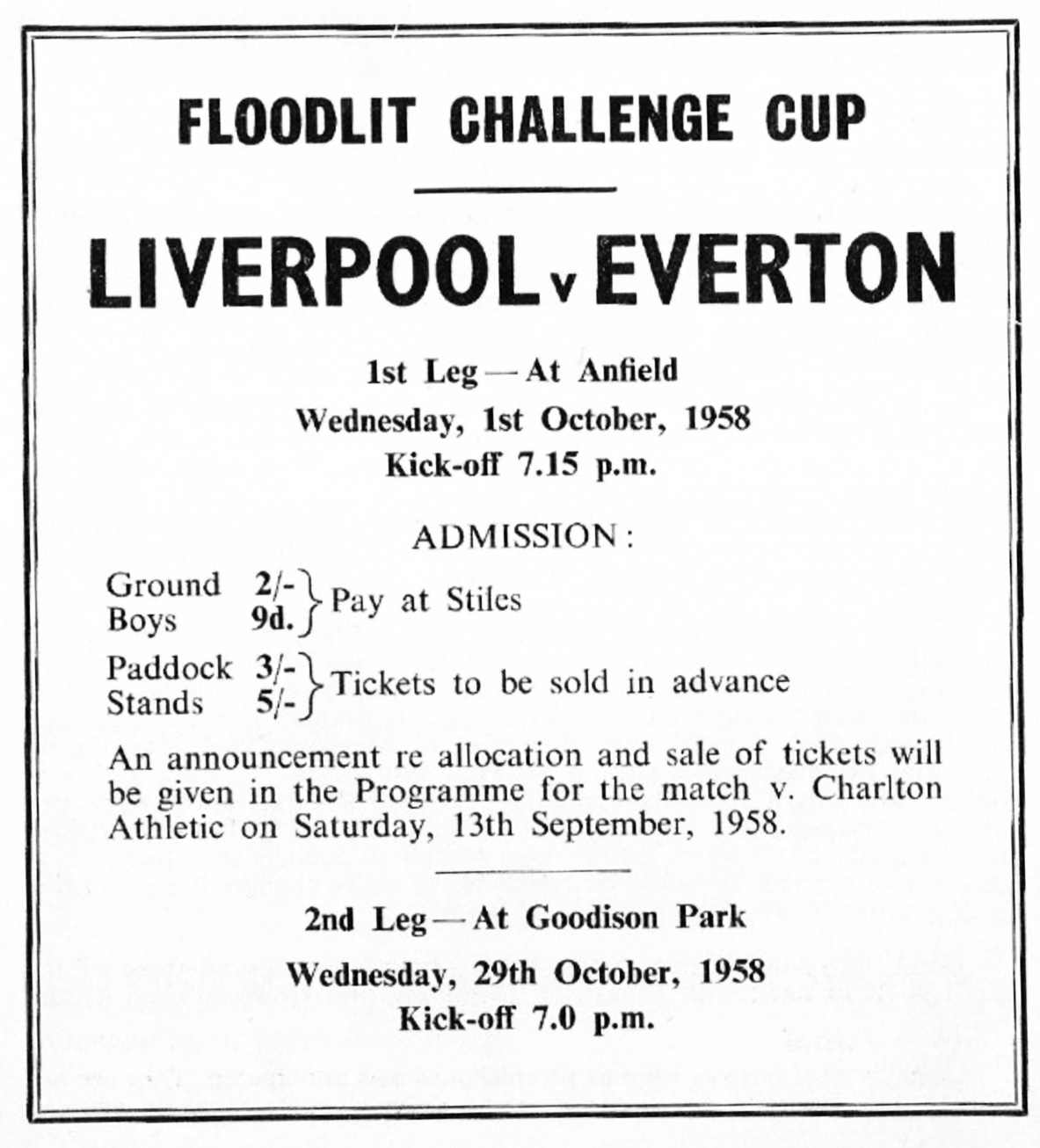

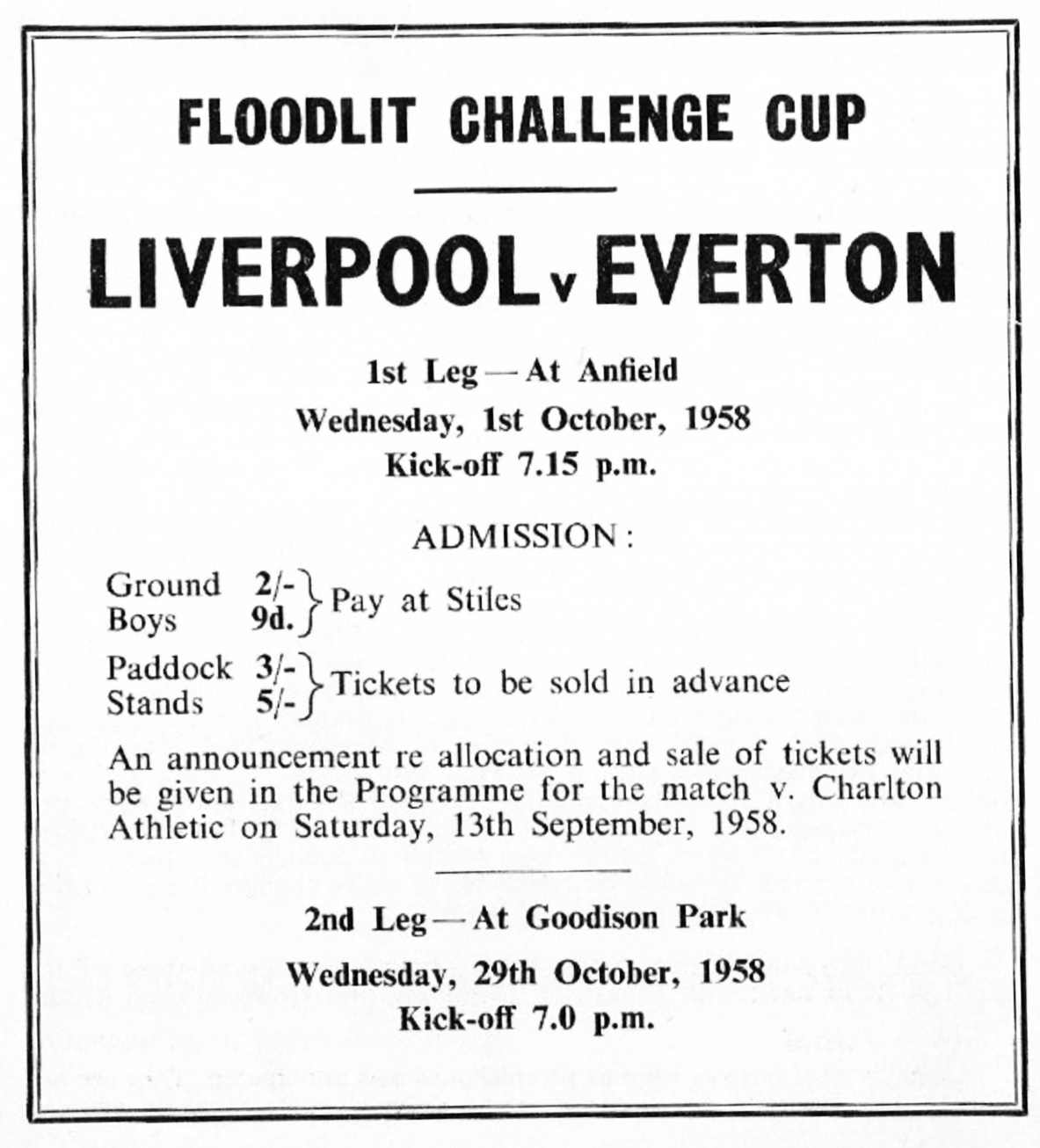

One set of friendlies, however, was new and directly related to the lighting – the two-leg Floodlit Challenge Cup between Everton and Liverpool. 8 October 1957 had originally been designed as an international opener to Everton’s much more expensive floodlights (£38,000 to LFC’s £12,000), but local influences appear to have prevailed. John Moores is believed to have lent money to both Everton and LFC towards the cost of the lights, and this Challenge Cup began the opening of

floodlit games in both clubs, on 9 and 30 October 1957, attracting over 100,000 fans. An ‘Echo’ headline predicted that 9 October at Goodison would be ‘the beginning of a new soccer era’. The beautiful £300 silver-gilt trophy (said to have been commissioned by the Lancashire FA) was to be held annually by the aggregate score winner, usually Liverpool who kept the cup permanently after the last game in the competition was played (18 October 1961).

The Floodlit Challenge Cup - © Stephen Done/Liverpool FC Museum & Tour Centre

This is now the only trophy of its kind from that era left in existence. In 1960, Coventry City was the last winner of the Southern Professional Floodlit tournament, and therefore kept the Cup, but Jim Brown, Coventry City’s historian, believes that it was destroyed eight years later (together with a located, but very distorted, Second Division trophy) in the main stand fire which consumed the trophy room at Highfield Road. Our Cup is not kept in the ‘over-full trophy room’, but at the moment in the Executive Lounge in the Main Stand.

*

The decision to go ahead with floodlights was a ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ gamble, taken by the much-maligned LFC Board of Directors which appointed Bill Shankly a couple of years later. The installation, with further upgrading in quality, was worth doing only in hindsight. The lights did not increase revenue for many years. Considerably improved technology did allow eventually for European success which, in the 1950s, no one could have predicted.

Article by Dr. Colin Rogers for LFChistory.net

Other articles by Dr. Rogers