Articles

The Ashworth enigmas

No headstone marks plot A0294 at Carleton cemetery in Blackpool; yet in this grave lie the remains of the mastermind behind some ten per cent of Liverpool’s top division league titles. I’ve been trying to solve some of the mysteries attached to his life, the principal ones concerning his origins, his character, the reasons for his appointment as LFC manager, his remarkable success in Liverpool, his sudden departure from that success, and why only one newspaper reported his death in 1947. Several earlier writers have offered solutions to all of these puzzles except, perhaps, the last.

Three birthplaces for David George Ashworth have appeared in print – Waterford in Ireland, Blackpool, and Poulton-le-Fylde near Blackpool. The Waterford possibility might have been a misreading of Waterfoot in Haslingden, where he spent some of his early life. Blackpool is correct (see Appendix for genealogical detail, including his birth entry, the only birth of a David George Ashworth in nineteenth century Britain. Notice, in particular, the death of his youngest sister, which might have contributed to his parents’ separation, and the deaths of two of his own children which might help to explain his concern for his daughter, the surviving child’s, welfare. Poulton-le-Fylde certainly had a publican surnamed Ashworth; but DGA’s father was a joiner at the time of his birth.

Both of his mother Maria’s grandfathers had been innkeepers, which might have influenced his father’s career move. Within a year of his birth, David Ashworth’s father William took over the running of a pub near the sea front in Blackpool, then still technically part of Layton-with-Warbreck. This occupational change was possibly the trigger for young David to be looked after by his paternal grandmother in Newchurch in Rossendale, while his younger sister Elizabeth went to stay with her maternal grandmother in Blackpool. By the time of the 1881 census, William and Maria’s family were reunited in the pub on Lytham Street, except David who continued to be brought up by his paternal grandmother who, I suspect, might have called him ‘Davie’, by which he was known for the rest of his life.

David Ashworth’s earliest occupation was in the manufacture of slippers, which were invented in Haslingden in 1874. By the 1880s millions of slippers were made annually, employing some 2,500 local people. I hope his sense of humour was tickled by eventually knowing that his son-in-law was called Shoesmith. The trade later went into decline, as a result of cheap foreign imports.

An early interest in football saw David playing for Newchurch Rovers, which in turn led him to become a qualified referee. Indeed, his earliest known connection with Liverpool might have been the match with Burton United at Anfield which he refereed on 1 September 1904. There was no national organization of referees until 1899 when the FA amalgamated twenty-seven local ones into one body. (The FA declines to answer questions on the subject.) This was a part-time occupation until at least 2001, and David remained a slipper machinist, living with his in-laws, until his appointment to Oldham Athletic in 1906.

*

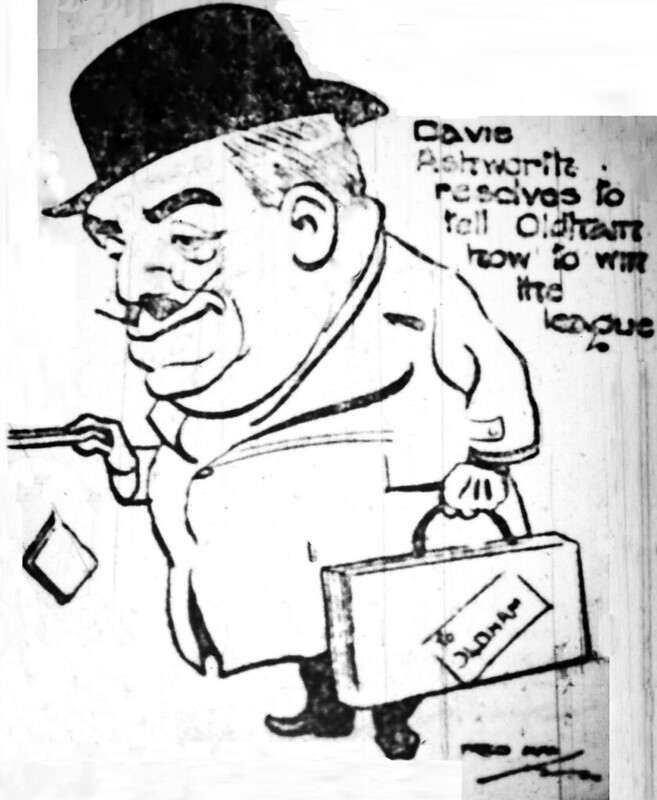

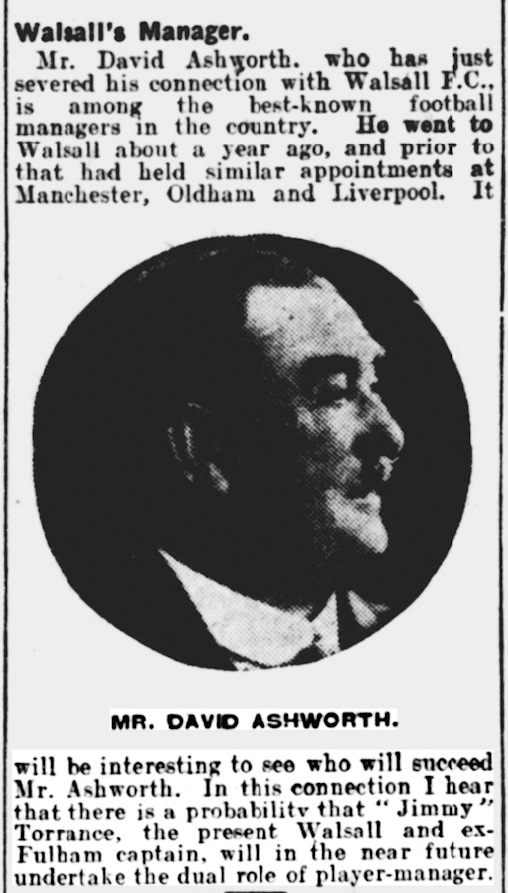

David’s character remains hidden by the normal practice at the time of appearing in photographs almost professionally and formally stern, with a bowler hat and well-groomed moustache. Reticence of match reporters on the tactics of named football managers does not help. Dig below the surface, and you will find a man with a strong sense of humour, an ease for making friends, his height – at about 5 feet, several inches shorter than his players – and beer belly not usually in evidence. His height makes him unmistakable in team photos. Like Tom Watson, said the Echo, he gets ‘a wee bit excited’ during matches. He was called ‘Davie’ by those who knew him and had strong interest in players’ welfare; a man who would twirl his moustache in different directions according to how well his team was playing – upwards for a win, downwards for a loss, one each way for a draw. He kept his travelling companions regaled with funny stories; a man who could not bear to watch penalties. (Now, who does that remind you of?) Look carefully at his posh photos – you might just see his pipe sticking out of his top pocket or a cigar in his hand.

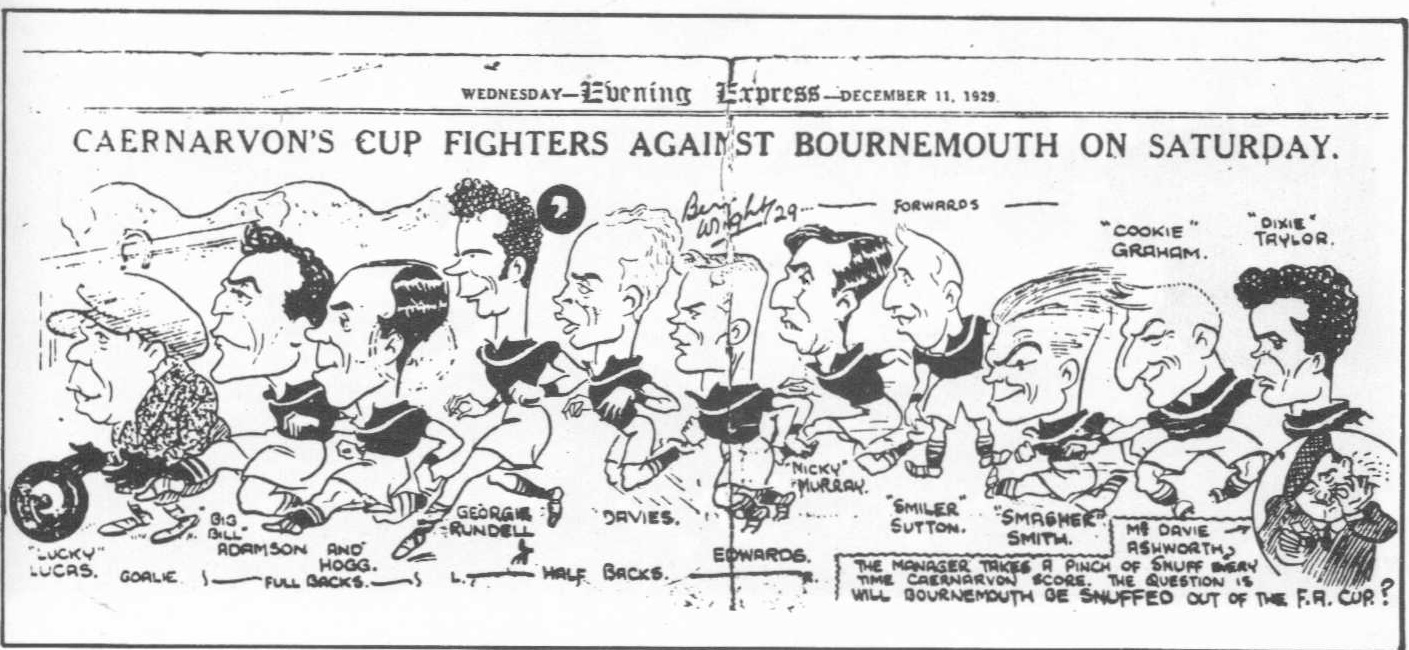

These idiosyncrasies made a gift for cartoonists – here he is, bottom right, while manager of Caernarvon Athletic! Note the flat cap and the portrayal for Ashworth's fondness for snuff.

Click image to enlarge

David’s success as first manager of the recently formed Oldham Athletic, playing in a 45,000 stadium, is well known and stood him in good stead to get future jobs. He remained at Oldham longer than at any other club in his managerial career. A season after he joined, the club was elected to Division 2 from which they were promoted to the top flight of English football in 1910. His overall record is 126 games won, 67 drawn, and 90 lost, a win ratio of 44.52%. (In the top flight only, during his last four seasons, 59, 42, 51, 39%.) Oldham were FA Cup semi-finalists in 1912/13, and they were good enough to come runners up in Division One, a year after he stepped down a division by moving to Stockport County on 30 April 1914. The Manchester Courier reported that there were a ‘very large number of applicants’ for the Stockport County job, but Ashworth was considered a ‘very suitable man for the post’.

County was then in Division Two, but in the final year of league football before the First World War, Ashworth returned to Anfield, this time as a manager of Stockport in the FA Cup. Liverpool won 3-0, clearly outclassing their opponents who did not help themselves by missing a penalty. The Liverpool Daily Post described Stockport as a ‘bustling side of triers’ who never gave up despite their position being ‘hopeless’ and ‘fighting a losing battle with almost Spartan-like bravery’. These rather unkind, though probably accurate, descriptions continued when the sides met four times in each of four seasons during the First World War. At first, the Echo and Daily Post were rather disparaging, reporter ‘Bee’ judging that ‘The County side, as usual, was a sturdy combination of plodders in which the spirit of strenuousness counted for much’. A year later (March 1917, after two draws home and away) County had improved to ‘brisk and businesslike’. Overall, in the first three seasons during the war, Liverpool and Stockport were neck and neck in the final tables, but thereafter Stockport fell well below LFC’s level.

Ashworth’s record at Stockport in the first post-war season does not seem so much better than his days at Oldham, winning only eight of his last eighteen matches with the second division club. So, we have another enigma - what did the Liverpool directors see in this man which caused them to have such faith in possible success on Merseyside as to seek him as their next manager? They certainly needed one – when George Patterson stepped down as manager to concentrate on his secretarial role, LFC was lying 18th in a 22-club top division, with relegation threatening. We had lost nine and won only seven.

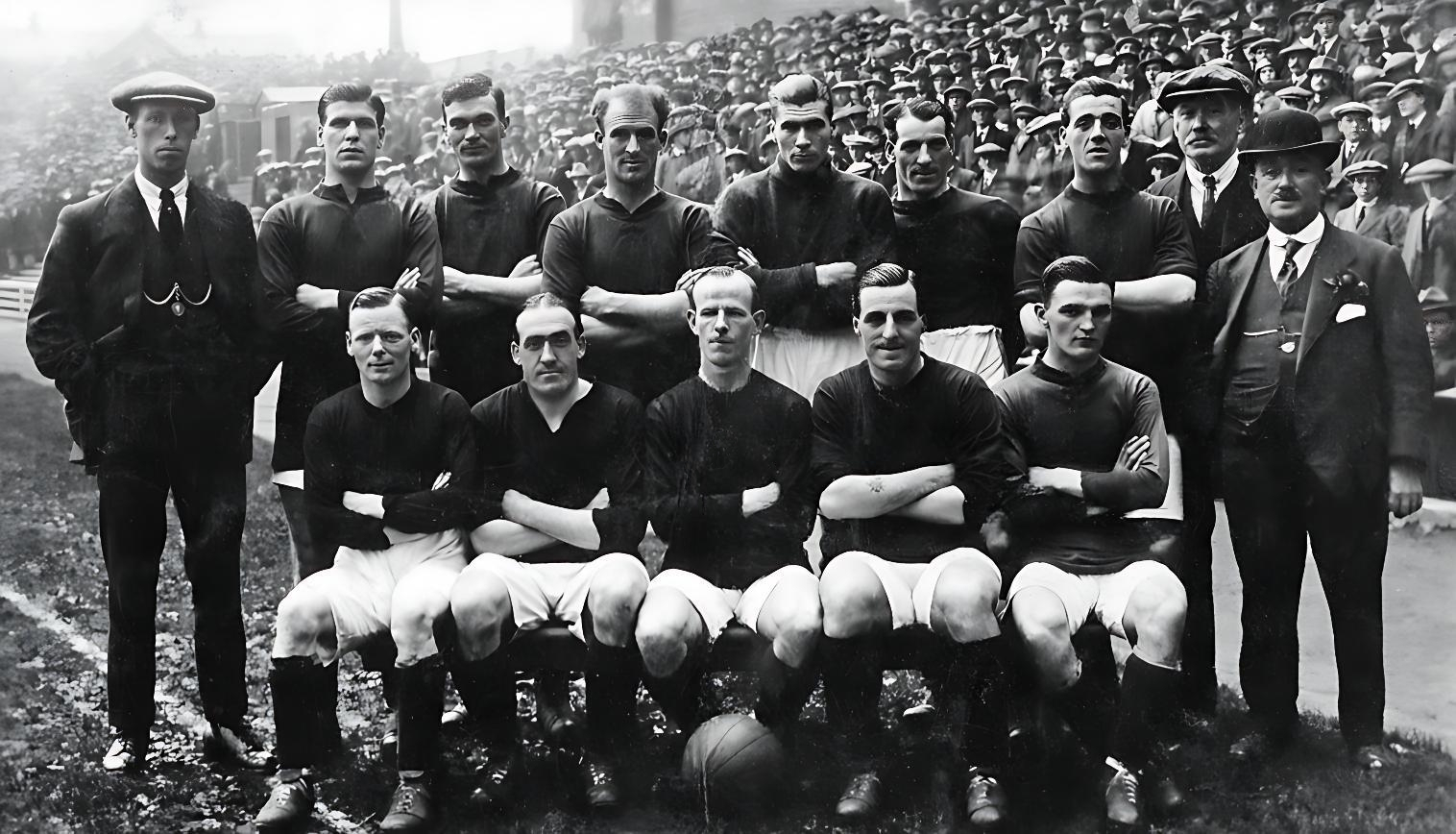

The Liverpool team in the 1919/20 season:

Back row: Dick Forshaw, John Bamber, Walter Wadsworth, Ephraim Longworth, Elisha Scott, Donald McKinlay, Tom Bromilow, William Connell (trainer), David Ashworth (Manager).

Front row Jackie Sheldon, Bill Lacey, Dick Johnson, Harry Chambers, Harold Wadsworth.

Being a well-known and well-liked figure in the north-west football world was not sufficient explanation, but the Liverpool directors clearly believed that ‘the man who made Oldham at cheap rates of payment’ had the tactical nous to improve the team performance without the need for investment in new players. Additionally, they should have remembered Ashworth’s record against them before the war – played 8, won 3, drawn 1, lost 4. GF 11, GA 9.

It worked! The effect was immediate and recognised at the time. David’s first match, on 20 December 1919 against Everton, a 0-0 draw, brought a Daily Post summary, ‘Liverpool were a well-balanced side, and their display was a great improvement upon any of their previous games.’ ‘Bee’ in Monday’s Echo agreed. ‘I have often expressed the idea that Liverpool had the men, and all that was needed was a welding process. Saturday proved the theory.’

After the last match of the 1919/20 season, the Liverpool Evening Express reported, ‘They finish fourth in the list [i.e. the league]; a very fine performance when we remember their early failure. Their revival dated from the Christmas Day match at Anfield against Sunderland, and it was fitting therefore, that the Reds should confirm this form at Roker. In the main, the Anfield brigade owed their success to a fine defence.’ (No mention of Ashworth’s recent appointment or contribution!)

The well-recognised stability of the Ashworth defence was quite remarkable and was undoubtedly one of the main foundations of his success. Scott, Bromilow, Lucas, McKinlay. McNab, Longworth, and Walter Wadsworth appeared in all his four seasons at the club, all being already in post when he was appointed. When Ashworth arrived, they had kept only one clean sheet; then, till the end of the season, they kept seventeen. Four other defenders (Jenkinson, Lowe, Pursell and Speakman) were allowed to leave at the end of the 1919/20 season when their contracts expired.

A less obvious advantage of this extended run with the same players is the experience they possessed in having to be played sometimes in unusual positions. This was no tactic only for emergencies. Very early in his Liverpool career, Ashworth was noted (not by name, of course) for encouraging his full backs to go forward, joining an attack if possible. By the start of the 1922/23 season, it was noted that McKinlay had played in every position on the field except goalkeeper!

The squad Ashworth inherited contained only one international (Bill Lacey), but each of these regular defenders, except Wadsworth, were first called up for their country during his short spell as manager, another testament to his coaching skills.

As for defenders appointed by the directors during Ashworth’s time at the club, two back-up goalkeepers did not stay long, and by 1920/21 the fearsome Elisha Scott was the only keeper in the squad after Ken Campbell left!

In another sign of his successor’s immediate impact, secretary George Patterson reported by February that he was ‘inundated with applications for tickets, having turned the corner in December’. The average gate for the remainder of the season rose by 6,000. Reporter ‘Bee’, however, apparently ignorant of the law of supply and demand, complained that Liverpool should not raise its prices just because it was doing well. Ashworth was already worth his weight, perhaps even in gold.

However, despite the closer cohesion in the defence, and the consequent rise in the Division table, the same could not be said about the forwards. They were being fed well enough by the half backs, but there was less cohesion among themselves. Only three lasted the four seasons with Ashworth as manager (Chambers, Forshaw and Lacey); eight new faces arrived in 1920/21, five in 1921/22, and two in 1922/23. Only three forwards became internationals during those years. There was more transfer of players further forward but, of course, managers were not responsible for signing them – nor indeed for picking them to play until the Shankly revolution.

The performance of the front line on the pitch was regularly criticized in the local press. At Huddersfield on 6 March 1920 ‘the full backs never put a foot wrong. Only the Liverpool forwards failed to impress' according to the local Liverpool papers. Huddersfield raised their prices for away fans who were ‘practically barred from getting tickets’.

Four days later [Sheffield] Wednesday visited Anfield, and a frustrated Evening Express concluded that ‘the Liverpool forwards should have had a field day, but the many chances provided by the halves were frittered away in amazing fashion. Some of the misses were inexplicable, and the home crowd became so “fed up” that they started shouting for the Wednesday…’ At the return game three days later, their shooting was ‘distinctly unfortunate’; against Oldham, they ‘lacked finish’ and ‘looked tired’; ‘finishing touches were lacking’ at Derby; and at West Brom, ‘defenders carried the honour of the day’ as the attack ‘needed welding together.’ (Daily Post)

The Liverpool and Manchester newspaper strike masks the first half of the 1920/21 season, during which Ephraim Longworth’s column giving defending advice began to be published. The relatively independent Athletic News then restarted for the first time since the war, providing evidence of steady if not spectacular progress in Ashworth’s full season as manager. Even on its first day back, it praised a Liverpool performance for a quality of football rarely seen at Villa Park. Nevertheless, the forwards continued to draw occasional criticism for too many misses (‘carelessly inaccurate’ against Middlesbrough, a ‘reckless and irresponsible attitude near goal’ when Blackburn visited Anfield), and sometimes not enough understanding between themselves. Against Bolton, it was specifically the wing men who let Liverpool down. LFC’s league position was maintained without being exceeded.

The directors, to their credit, took notice of these criticisms, and played a trick which converted two good league positions into the best. I wish I could prove that Ashworth was behind the scheme, but he turned their purchase into a move of genius. The icing on the cake (for a modern fan) is that we had Manchester United to thank for it. At the end of the 1920/21 season (22 May), LFC bought a 26-year-old outside-left Fred Hopkin from Old Trafford. (According to alchetron.com, ‘Hopkin was signed by Liverpool manager David Ashworth for £2,800’ which might suggest that he had been responsible in practice.) It was not a case of MUFC unloading a rarely used or undervalued player – he had played 74 times since the war but scored only eight goals. United had even illegally overpaid Hopkin and been fined for doing so. His spell at Anfield lasted ten years, during which his goal scoring ratio considerably worsened to one goal in 30 games!

David Ashworth with Donald McKinlay, Walter Wadsworth, Jock McNab, Bill Lacey, Fred Hopkin, ? and Tom Bromilow (left to right).

Assessments in The Athletic pinpoint the way Hopkin ('the only expensive member of the side’) was exploited to best effect by Ashworth. Their end of year assessment on him included the telling sentence, 'Hopkin never had such support in his former club’. Even by November 1921, it expressed surprise that United had let him go. At Sunderland in the New Year, ‘Hopkin was extremely fast and clever at outside left. Considering how he played at Manchester United, his consistency week-in, week-out is a puzzle. He never wastes time and gets the ball near the goal area, nor does he ever show any sign of having too much to do. …there is a marked development in his football compared with 18 months ago.’

The contribution of Hopkin’s first season with Liverpool can now be quantified as a result of research into assists. He can be shown to be directly involved in at least twenty goals without scoring one himself, and ten more before Christmas 1922 – for comparison, no LFC player had more than 13 assists in 2023/24.

The Athletic’s conclusion included: ‘…from what I have seen of the Anfield combination they are worthy of the honour because of their team spirit, their unity, and that strength which comes from the great essential of all football – skillful fellowship’. ‘They rely on intelligent combination rather than theatrical displays.’

They had remained top of the table from December 1921 and could still afford to lose five league games in March and April, finishing six points clear of Spurs in a two-for-a-win system. The story of that season on the field is detailed in this article on LFChistory. Once again, through our modern eyes, the manager’s name was missing from match reports, as if he was an also-ran in a title race.

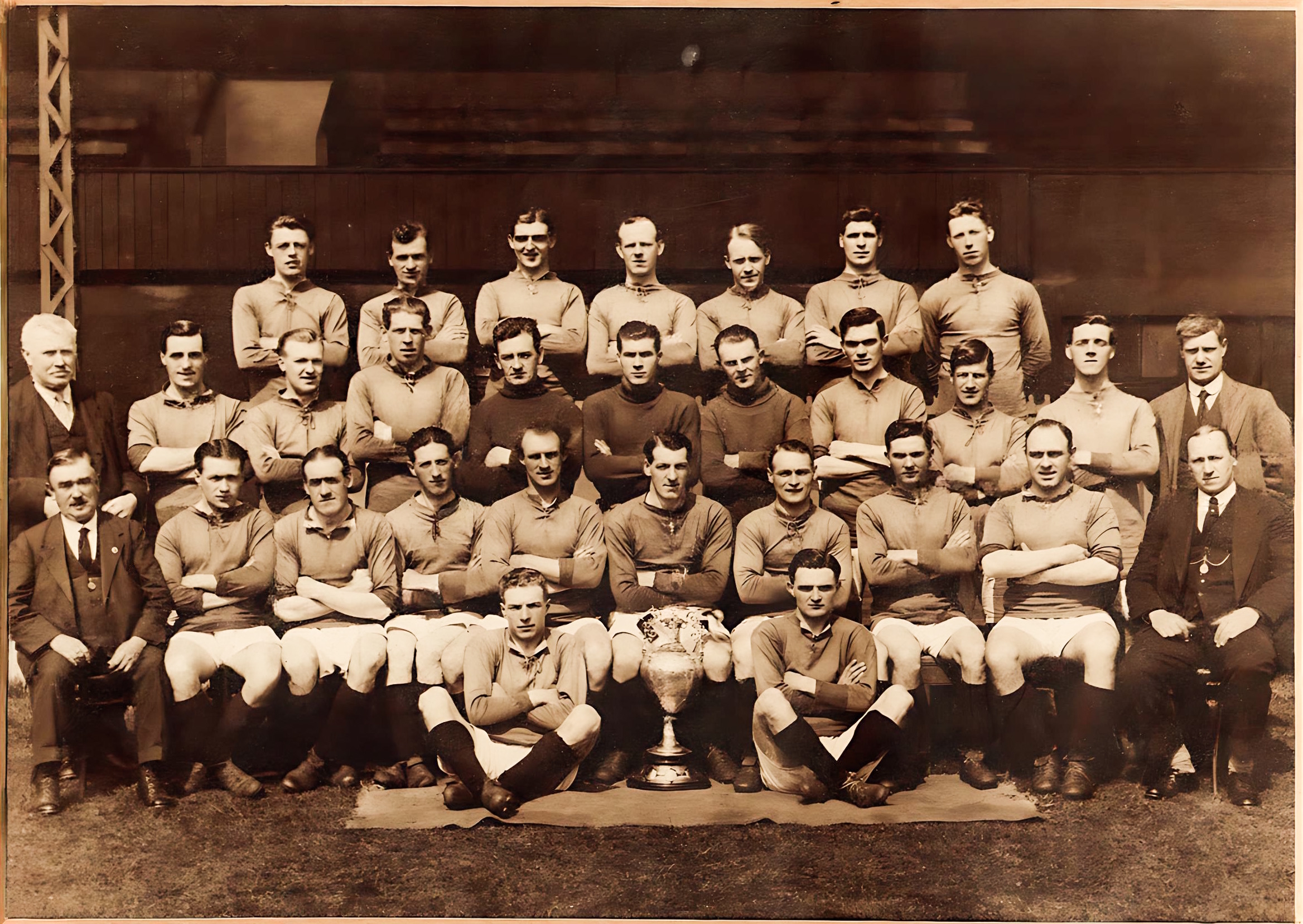

The 1921/22 team with their league title

Back row: Cyril Gilhespy, Bill Cunningham, Peter McKinney, Dick Johnson, Francis Checkland, John Bamber, Dick Forshaw.

Middle row: William Connell (Trainer), Harry Chambers, ?, Jock McNab, Frank Mitchell, Elisha Scott, ?, Walter Wadsworth, Harry Lewis, Tom Bromilow, Joe Hewitt (Trainer)

Front row: Dave Ashworth (Manager), Harry Beadles, Bill Lacey, Ted Parry, Ephraim Longworth, Donald McKinlay, Tommy Lucas, ?, Fred Hopkin, George Patterson (Secretary).

On ground: Danny Shone, Harold Wadsworth

The following season was even better. After a slip-up at Highbury, from which Hopkin was noticeably absent, they amassed twenty-six goals in the first nine matches, as they reached the top in September 1922 and stayed there until May 1923.

A rare event occurred on the sixteenth of December 1922 when Ashworth’s name appears in a match report. The Athletic’s reporter ‘Harricus’ was taken onto the pitch and invited to judge the light before the club decided to open the ground. The date of that might not be a coincidence. Three days later, The Echo’s ‘Bee’ says that Ashworth had asked him to deny rumours that he was going to resign and return to Oldham Athletic as their manager. ‘Bee’ had to eat his words a day later, and the official announcement of his departure appeared in the Evening Express on 22 December. The Directors could not have known that they had hired a ticking time bomb when his family did not come with him, preferring to remain in Stockport almost next to Stockport County’s ground – yet they had joined him there from their Oldham home five years earlier.

There had been a steady progression during Ashworth’s four seasons at Liverpool, highlighted by the final results tables. In 1919/20, ten other clubs scored more goals than LFC; the figures for the next three seasons were eight, six and two (Sunderland and Cardiff). In contrast, the goals against figures show only one club (Newcastle) let in fewer goals than Liverpool in 1919/20, and none did for the next three seasons. There is some evidence that Liverpool benefited from the volatile fortunes of some other clubs. West Brom, who scored a remarkable 107 goals in winning 1919/20, fell to fourteenth in 1920/21. Chelsea was third in 1919/20, but a lowly 18th in 1920/21. Burnley, who was dominant in the tables from 1919/20 to 1921/22, fell to 15th in 1922/23. During those four seasons, only three other clubs (Aston Villa, Manchester City, Newcastle United) remained in the top half of the final tables.

| Season | For | Against | Points | Pos. |

| 1919/20 | 59 | 44 | 48 | 4 |

| 1920/21 | 63 | 35 | 51 | 4 |

| 1921/22 | 63 | 36 | 57 | 1 |

| 1922/23 | 70 | 31 | 60 | 1 |

*

David Ashworth’s sudden departure from a position which must have been the envy of every other manager in the country to an Oldham Athletic then twenty-first in the same league, and the lack of acrimony in the club which he was leaving in the lurch, have not been easy to explain. Two theories have been put forward. The less convincing is that he had an inclination to help an underdog, and Oldham (a club he had nurtured from its birth) was in trouble at the time. Oldham had recently been re-formed when he joined in 1906, but he stayed for eight years with considerable success. Stockport County was in Division 2. Liverpool was also in some difficulty when he joined in 1919. However, changes in his subsequent managerial career are more easily explained by failures (especially financial) on the football pitch rather than a figure of a knight riding to a damsel’s distress.

The Echo quite formally told readers that the Liverpool board agreed to defer for one week a decision whether to accept his request to be released early from his contract which expired in a few months’ time. This was no explanation, of course. Perhaps the U-turn from what they had reported earlier on 19 December (claimed as a scoop) still rankled with the paper.

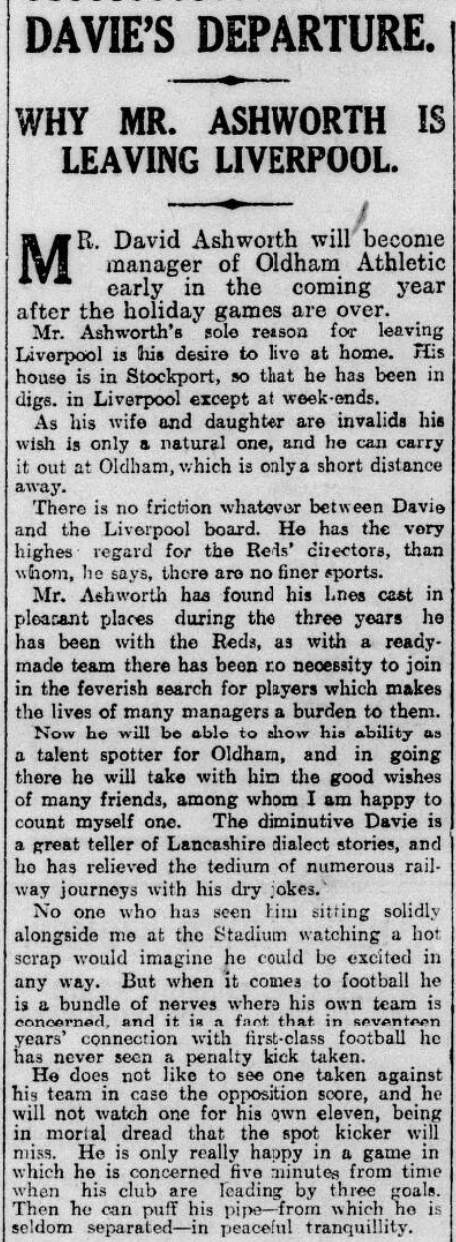

A second, much more personal, reason for his departure, and the one which he offered to the club at the time, appeared in an Evening Express article on page 6, 22 December.

‘The men who made Liverpool’ series also has his family’s illness as a reason for his departure – but illness and invalidity are not synonymous. Why was he living apart from his family in Liverpool digs anyway? Why, having moved from Oldham to Stockport in 1914, had they not come with him to Liverpool?

The suggestions which follow, while being only my personal guesswork, seem to fit the facts. In Stockport they lived a stone’s throw from the Edgeley stadium. Now, Ashworth was away from his wife for long periods, not just the travelling to Liverpool from Stockport, but also the frequent away games, and even going on holiday with the players. (The Evening Express tells of one holiday with thirteen players to Whitley Bay after strenuous games over the 1919 Christmas period.) Many wives would have raised more than an eyebrow at such an arrangement. Perhaps the invalid status was just a pretext – I have no way to prove it, and no reason to doubt it, though daughter Nellie was certainly fit enough to work in Fred Armitage’s bakery further down Stockport’s Castle Street in the summer of 1921.

Perhaps, as a young teenager (she was 13 when they moved to Stockport), daughter Nellie had developed friends there and, as their sole surviving child, twisted her loving parents’ arms to let her stay. Furthermore, and regrettable as it is to conclude, even before Nellie had reached adulthood in 1927, David Ashworth’s desire to be with his wife in Stockport had apparently diminished. They moved from Castle Street, Stockport between October 1923 and 1924, although Manchester City was closer than Oldham. Did he blame her (or them) for forcing an interruption in the successful career he loved? It is not hard to imagine how he must have felt when he saw LFC celebrate another (really his) First Division title while he was accompanying Oldham down into relegation. Far from remaining together as a family, he moved to Walsall in 1926, Caernarfon Town a year later, and Llanelli in 1930. He is reported to have become a scout for Blackpool by 1935, and when the second world war broke out, he was still in Blackpool, and wife Annie had returned to Haslingden. I am sure that he gave up Liverpool for family reasons – but the exact nature of those reasons remains undiscovered.

*

Rarely has a managerial career gone downhill so quickly as that of David Ashworth. He’d had no break from the sport, but now, for the first time, results were not commensurate with his skills. Whatever caused his sudden departure from Anfield, ostensibly in order to manage Oldham Athletic again, has a lot to answer for. That love for success on the field was still there for all to admire, but the win ratio during his second spell at Oldham was the worst in his managerial career (31.75%) and the club was relegated at the end of his 1922/23 season after losing twelve of the next twenty-two games. In Division 2 his results were not inspiring - won 15 / drew 17 / lost 12 (34%).

A sixteen-month spell as Manchester City manager followed from July 1924, presumably recruited on the basis of his success with Liverpool. Whatever his motive, he could hardly be accused of trying to rescue an underdog – City had just finished 11th in the First Division. His was summarized by ‘Blue Moon’ as ‘probably the first City appointment that actually failed.’ Though he never won again at Anfield, that spell included a 5-0 thrashing of his old club at Maine Road! No club scored more (68) in the First Division, but finished only tenth, and on 24 November 1925 the Board accepted his offer to resign subject to a financial package before his contract ended in July. He is not fondly remembered in Manchester City’s histories (if indeed he is mentioned at all) though he did recruit one of their stars, Sam Cowan, who’d only just joined Doncaster at the time. City was the only club failing to express regret at his departure.

‘What he doesn’t know about football isn’t worth knowing'

Ashworth’s last three clubs were increasingly further away from the Manchester area. At each, his reputation from Oldham and especially Liverpool went before him. ‘What he doesn’t know about football isn’t worth knowing’ is a sentence appearing in more than one welcoming town. He was portrayed as the saviour of Oldham by quitting Liverpool to accede to their wish to be rescued from their ’falling fortunes’ (but without mentioning that he failed), and had left Manchester City after resigning ‘on a matter of [unspecified] principle’.

Walsall, however, was not a good choice for him. The Walsall Observer expressed surprise that they had been ‘extremely fortunate’ to secure his services, since the club’s outlook is ‘as black as it could possibly be’. Admittedly Davie was a footballer, not a financier, but even he should have predicted financial trouble in a smaller town in Third Division North, situated in the Birmingham, West Bromwich and Wolverhampton conglomeration. A crowd of under 2,000 saw their last match of 1925/26. He started a Supporters Club with the main object of raising funds, without which he saw that Walsall could not pay for players capable of lifting them into Division 2.

Attendances at Walsall doubled at first, but even though he was allowed to choose the team, new manager bounce did not last long, and some directors had to pay the players’ summer wages from their own pockets. Far from seeing Ashworth’s new players – some from Liverpool (including Ted Parry who was capped for Wales on 13 Feb 1926) and Oldham – as the foundation of a rise to Division 2, the directors saw them as a means to make a quick profit, ex-Liverpool international Archie Rawlings being sold to Bradford after only 23 appearances. The Watford Observer also noted that ‘some of his swans turned out to be geese’ and, amid falling gates, Ashworth resigned in February 1927. I have not discovered the nature of his employment until he joined Caernarvon sixteen months later – presumably he could fall back on unemployment benefit, a consequence of which might have caused him to accept the Walsall job in the first place. He was replaced three months later by James Torrance, one of the players he had recruited.

The Liverpool Evening Express evidently took an interest in David Ashworth’s career, on 6 June 1928 making a note on his appointment at Caernarvon. (The same paper is seen elsewhere in this article concerning his departure from Anfield, and indeed his departure from this life, the only paper to do so.) He almost certainly chose Caernarvon in response to a nationwide advert for a new manager, and in turn used the same method to recruit new players.

Athletic News 4 June 1928

Caernarvon Athletic would have been insulted if referred to as ‘underdog’. Here, he acquired a specific description ‘manager-trainer‘ of the team which was already top of the Welsh League North, and did not lose a home match for two years. The club’s total wage bill was £40 a week in a town of only 10,000, a feat which was described in the local paper as one of the ‘little marvels of the football world’. Running the club so cheaply was still too much for the limited company which owned it, and they became insolvent in 1930.

An extraordinary insight into Ashworth at work was published in the Carnarvon & Denbigh Herald, perhaps in a mockingly valiant Welsh attempt at his Lancashire accent, supposedly overheard in a barber shop. ‘Ave watched him at t’Oval [i.e. home ground] looking on and trying to find ‘aht t’weak points o’ th’ players. And when they score aht comes t’ snuff box, and then a cigarette. At hofe time he has found t’weak spots in t’visiting lot, an’ he goes and tells his boys. Ah, Davy is a great little man, ah can tell thee. He comes fra Owdham, good old Davy.’

1930 proved a bittersweet year, however, when his team was top of the Welsh National League North again with a fine record: played 24, won 18, drawn 4, lost 2. Goals for 103, against 26. They entered the English FA Cup for the first time, being beaten by Bournemouth in a second round replay. However, reconstruction of the already complicated organisation of soccer in Wales led to the feared, predicted demise of Caernarvon AFC; Ashworth had to abandon ship. Losing him was a great regret for the town. A former club secretary is quoted as saying, ‘What he did not know about football was not worth knowing. He had the experience, whilst others had only the theory, and it is said that an ounce of experience is worth a ton of theory.’

The former club secretary, Sammy Vaughan Jones, averred that ‘Ashworth 'bach' was regarded with affection. These guys were still talking about him and his pro team 50 years later.’ He had a room in Paternoster Buildings, 22 Castle Square, which does not sound conducive to family life. (He, like the players, probably had to live in the town.) There he gave a farewell interview, reeling off the nine games in the English FA Cup which they had entered for the first time. Amid the debate on the future of soccer in north Wales, Ashworth had his interesting view on players’ wages published, another rarity for the times, saying that he was against a proposed maximum wage (say £15 or £20) for players preferring a minimum wage of not less than £12 a week.

*

The first mention of David Ashworth at his final club as manager was on 28 June 1930 when he was announced as the ‘new secretary of the Llanelli Soccer Club’. As in Oldham and Caernarvon, he had to compete with rugby for fans, but it was typical of the man that he wanted to collaborate, taking the trouble to go to London in order to arrange for the dates of home fixtures not to clash. He was an honoured guest at a rugby club dinner.

He soon had his teams playing ‘delightful football’ with great ambitions, including promotion to the English Division 3. His reputation in the game was such that he was invited to join the Directors on a visit to Tottenham Hotspurs seeking help towards the necessary funds for a new stadium.

One lovely story from his time at Llanelli is his solution to the sometimes dangerous ways in which local children used any means to see the games free of charge. He argued that they should be allowed into the ground, to a specially designated area, for one penny. Even that, he argued, would increase the club’s revenue by £75 a year, saying, ‘There is not a club in South Wales which can afford to disregard such a sum.’ A similar suggestion had been successfully put into operation as the Boys’ Pen at Anfield, only a few months before Ashworth’s sudden departure.

During his first season, ‘Llanelly’ (as it then was) reached its best league position before the 1950s, scoring 72 goals in a 22-match season in contrast to 55 in 28 games before his arrival.

His reason for leaving his last managerial post remains a mystery. On 5 December 1931, the ‘Star’ and ‘South Wales Daily Post’ reported his resignation without explanation.

*

Why return to Blackpool? He was 64 years old, and presumably looking for part time work – scouting for the Bloomfield Road club would have been seen as an excellent solution, to use his skills in a less phrenetic environment despite not being on the phone. (He would have to use the club’s phone at Blackpool 325). Perhaps, knowing his own birthplace, he had been a Blackpool fan. The club was promoted from Division 2 in 1937 and maintained a respectable position in the league until the 1960s and the end of the Stanley Matthews era which began on 10 May 1947.

Separated from his own parents so young, and too early to benefit from ‘You’ll never walk alone’, Ashworth seems to have died alone, and he left an estate too small for probate. ‘Causing the body to be buried’ is the last of a line of people who are legally qualified to be the informant at a death registration, though ‘E. Hughes’ was Elizabeth Hughes, probably the same Elizabeth Hughes with whom he was living on Central Drive, Blackpool, in 1939. (She was 27 years younger than Davie, possibly his landlady.) In one final enigma, she had bought the grave. His daughter Nellie chose not to be the informant in 1947 even if she knew about his death.

He is even the only inhabitant of his grave in Carleton cemetery. Surely it is time that he is given a headstone, a reminder of one of Liverpool’s greatest achievements.

Written for lfchistory.net by Dr. Colin D. Rogers - Copyright LFChistory.net

With thanks for help from Neil Dymock, Ian Garland, Aled Bont Jones, Geraint Jones, Roy Whalley, and (as usual) Dudley Harrop.

CLICK THE NEXT PAGE TO SEE DAVID GEORGE ASHWORTH'S GENEALOGICAL APPENDIX