Articles

Justice for the LFC Twelve (and many others)

Phil Taylor scored two goals against Middlesbrough in 1939

There seems to be an anomaly in the summaries of a few former LFC players on the lfchistory.net website. Take Matt Busby, for example. The personal data in the players’ section shows that his last appearance for the club was on 6 May, 1939. Yet, in the 1939/40 First Division games, he played on 26 and 30 August, and 2 September 1939.

He is not alone – there are three others in a similar position. Goalie Dirk Kemp’s ‘last’ appearance was on 11 February 1939, and the dates of Jimmy McInnes and Harman van den Berg are the same as those of Busby. All are shown to have played in the same three matches later in the year.

Eight others were involved, but also played in post-war matches. The ’LFC twelve’ are those listed below who played in the three matches, but whose contributions have been expunged from their official records kept by the Football League, a decision also followed by many if not most of those keeping individual club records and by the Association of Football Statisticians. The full list, with the number of matches played (and goals scored) is:

| NAME | Games | Goals |

| Jack Balmer | 3 | 2 |

| Matt Busby | 3 | 0 |

| Tom Bush | 3 | 0 |

| Cyril Done | 1 | 1 |

| Willie Fagan | 3 | 0 |

| Jim Harley | 3 | 0 |

| Dirk Kemp | 3 | 0 |

| Jimmy McInnes | 3 | 1 |

| Berry Nieuwenhuys | 3 | 0 |

| Bernard Ramdsen | 3 | 0 |

| Phil Taylor | 2 | 2 |

| Harman van den Berg | 3 | 0 |

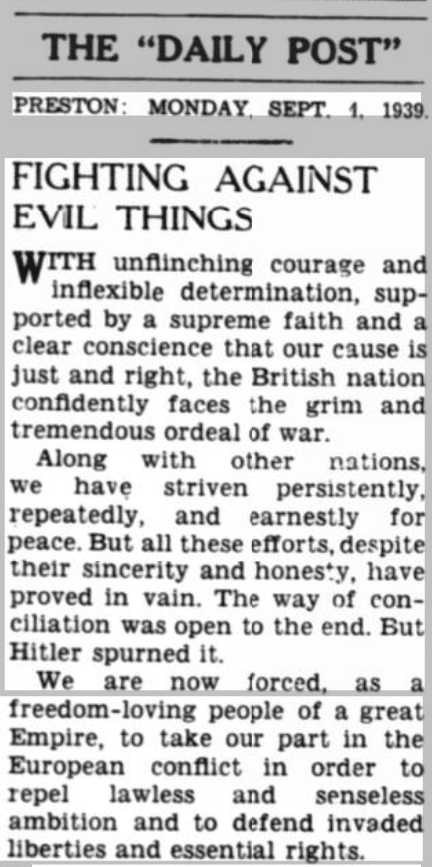

The clue as to the cause of the anomaly, is not hard to find. On the day before LFC’s Bramall Lane game against newly-promoted Sheffield United on 26 August, Germany’s allies invaded Poland. Four days later, as LFC was beating Middlesbrough 4-1 at Anfield, Nazi Germany issued an ultimatum to Poland, and actually invaded the country the day before our home success over Chelsea on 2 September. Even then, the Home Office had advised the FA that there was no reason to stop the 2 September games from going ahead. Football was determined to continue, until it was ordered to stop – which it did, being suspended on the orders of Chamberlain’s faltering and discredited government, one day after we declared war on 3 September. (Jim Harley, the LFC full back once described in the Echo as ‘Football’s finest built man’, also declared war (on Chelsea) and was sent off for punching David James, their centre-forward!)

The Civil Service had been quietly preparing for war for years, recruiting 65,000 data collectors so they would be ready to implement a National Registration Act, the basis for our wartime ID and ration cards (and eventually even the National Health Service register). Lessons from an earlier 1915 version had been learned. The collectors registered over 45 million people in a few days. In great contrast, football was torn between conflicting interests, not all of which sat easily with the government’s main objective – to keep the people as safe as possible. From the lessons of the Spanish Civil War, it was believed that, in sharp contrast to the threat in 1914, bombing would be immediate, and what easier target than 30,000 or more at Anfield at 3.00 on a Saturday afternoon? (Several grounds were damaged during the blitz, including Old Trafford and Bramall Lane.) Now, it looks as though English football had remembered too well continuing to play during 1914/15, and assumed the same casual reaction might apply in 1939/40 – whenever another war broke out.

Organising the closedown of football was as chaotic as it was unplanned. The Home Office (England and Wales) effectively terminated the contracts of all managers, players and staff on 3 September with the suspension of all games until further notice, though former professional players had to remain on their club’s books until the war ended. Players, some worth thousands of pounds on the first of September, were worth nothing a week later. They weren’t even allowed to return to their earlier, amateur, status, in order to get some game time.

Adding to the chaos, clubs were asked to keep their players ‘on standby’ in case the war ended quickly and the 1939/40 season could be resumed. Lists of players whom clubs wished to retain on this basis were sent to the FA annually. Some lawyers put in their two penn’orth by pointing out that the contracts cannot be legally made void if the season itself had not formally been abandoned, which did not happen until 18 September when all hope of completing the season vanished.

On that date, the Daily Herald reported that, ‘During the last two weeks, club officials have been utterly bewildered by the confusing statements which have been issued from time to time…. There is widespread discontent at the hopeless confusion which so far has characterized most of the official football announcements.’ The Daily Express called it ‘a most ghastly mess.’ Meanwhile, other spectator sports (even greyhound racing) were looking to football, the most popular, for a lead on what to do! Sailing came off worst, with a ban on coastal yachting.

Lancashire Daily Post 4 September 1945

Under pressure from those involved in the sport, football was allowed to resume fairly soon when Nazi bombers did not appear in British skies, but at first only on Saturdays, and with an upper limit of 3,000 spectators. (Pressure from within the sport got it increased to 5,000, with each game getting prior police approval and ‘definitely’ no more than 8,000 fans!) A fifty-mile travel limit effectively ended the normal league programme which, after weeks of argument, was replaced by regional competitions, thus finally sealing the fate of the three games already played. Liverpool was in the Western League for the rest of the season, with Barrow, Chester, Crewe, Everton, Manchester (City and United), New Brighton, Port Vale, Stockport, Stoke, Tranmere, and Wrexham. At first, even friendly games were barred in many places including Liverpool, Birkenhead, Bootle, Runcorn and Wallasey, for fear of attracting large crowds.

The Home Office also put restrictions on players’ wages and entrance fees, partly to prevent football owners making a profit during the conflict. Wages had halved from pre-war with a new a ceiling of £2 per week (First Division) a pound less for Division 2. Referees got one guinea (!), linesmen 10/6 (i.e. half a guinea).

Thus, the interests of the Football Association with its War Emergency Committee, the Football League, Boards of Directors, and the players’ union went counter to those of the Home Office. Justification to the public for continuing the sport was on the basis of trying to keep a bit of normality in otherwise wartime conditions, and keeping young men fit and healthy for the fight to come as well as being able to pay their mortgages. The reality, however, was their dread that the very fabric of professional football was threatened because clubs faced financial ruin without the regular income from turnstiles. Attendances at Anfield for the two home games (Middlesbrough and Chelsea) were already down by forty per cent over the same opponents in 1938/39.

*

The confusion in the story so far, with the number of interested parties and conflicting objectives, plus the necessary emphasis on what should happen next, has masked the question of the status of the three games already completed. They were now in limbo. One quickly-discounted possibility was to accept 1939/40 as a three-match season, which would have given Blackpool the title. Huddersfield Town’s statistician, Alan Hodgson, quotes the League Management Committee as declaring that ‘League matches already played are to be counted as cup-ties, and if the regular schedule resumed later, the return matches will be played on similar terms.’ The Football League, however, was not in charge of the FA Cup! Relatively modern articles include phrases such as all results to date in the 1939-40 season being declared ‘null and void’, or matches were ‘wiped from the records’, which convey the result of what happened, but I have been unable to pin down a date or level of formal decision making for either ‘null’ or ’void’. I’m not even sure that a football match can be legally ‘null and void’, which are terms relating to clauses in a contract. One article says that the season was declared null and void by the FA, but the source quoted does not support that. Meanwhile, the Players’ Union (now the PFA) was far more concerned with negotiations over wages than worrying about the status of the three games completed! (Their fight over wages continued after the war, including the threat of strike action, and the welfare of members who remained ‘redundant war workers’.)

The 1939/40 season Liverpool squad:

Back row: Jimmy McInnes, Phil Taylor, Jim Harley, Dirk Kemp, Tom Bush, Bernard Ramsden, Tom Cooper.

Front row: Berry Nieuwenhuys, Willie Fagan, Matt Busby, Jack Balmer, Harman Van Den Berg.

Details of the three matches, including LFC players’ names are given in lfchistory.net, with the following cautionary note:

‘The three league games played in the 1939-40 season were expunged from Football League records as the season was stopped due to World War II. The games are therefore not considered valid by lfchistory.net and as the "Association of football statisticians" does not count them towards official player totals.’

Yet Liverpool’s three matches were played officially as first division games, and just because the competition itself was abandoned, I see no reason why the players’ contributions should not be acknowledged. Ask Chelsea’s David James for confirmation! History is, at the very least, a record of what happened, and giving 6 May as Busby’s last game for Liverpool is simply not true. (What’s that well-known saying about statistics?) In common with other clubs’ historical accounts, lfchistory.net feels it cannot acknowledge that the matches were part of the players’ careers (hence the ‘last appearance’ of Busby, Kemp, McInnes, and van den Berg was before the 1939/40 season) and perhaps even worse, Busby’s newly acquired club captaincy is now missing from his club and League record. The English National Football Archive takes a much more charitable solution in their own record system, providing the data of the three games while marking both the distinctive nature of the games and the players concerned. The FA’s archive of the Extra Preliminary Round of the FA Cup lists the 2 September 1939 results, with goalscorers where known.

However, ‘expunged’ simply means ‘removed’, not ‘didn’t happen’. Claiming that we should behave as if an event did not happen smacks of political correctness at best, totalitarianism at worst. To me, declaring that the matches never officially happened is an insult to the players concerned, especially when, AT THE TIME, they DID officially happen, and to people (players and other staff) who were doing their best for LFC in the most extraordinarily fraught circumstances ever played by professional football. And what about those often forgotten twenty-third men on the pitch? Were the careers of the three referees (Messrs Ross-Gower, Berry and Jones) expunged by the FA? The Referees’ Association could not help.

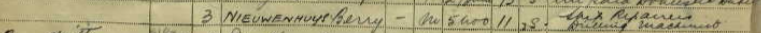

By the Sheffield game on 26 August, twenty-two Liverpool players were in the Territorials; others had been drafted into the war effort –for example, ‘Nivvy’ and Harman van den Berg were working on the docks, repairing ships; half-back Fred Rogers, a painter and decorator of ‘Anfield’ in Ship Street, Frodsham, was drafted to paint camouflage.

![]()

![]()

(entries from the 1939 National Register)

Twenty of Liverpool’s twenty-nine professionals, including ten of the twelve who played in the three matches, were called up the day before the Middlesbrough game, but were able to play because they were training locally; by 2 September many were in camps far away from the city, some reported as having to get up at 5.00 a.m. to get to the game on time. They were fighting two campaigns at once; yet there was no deterioration of quality of players selected from the previous season, despite those difficulties.

Daily News (London) 4 Sept. 1939, entitled ‘Away fixture’ by Mercer.

In seeking to examine the contemporary arguments for and against this removal of the three matches from official records, I tried in vain to find the date on which the decision was taken. Neither the FA nor the (E)FL, nor the Association of Football Statisticians Association, nor the National Football Museum have been able to provide an answer. No such date has emerged in correspondence from football historians who know far more than I ever will (some the authors of articles on 1939); 1939 and 1945 newspapers do not carry reports of such a momentous decision. I have not found any example of a club being informed by the FA or FL that records should be deleted. Were players even informed that their records were to be expunged? And I still can’t quite work out whether, by having their national record deleted, the players were being punished for something it was believed they hadn’t done, or for something they had done!

What the government declared in 1939 was the suspension of the season for remainder of the competition, not the first seasonal games already played or the players’ records. When contracts were ‘suspended’ in September 1939, those for the three completed matches were not affected. Players and staff were not asked to refund their wages because the matches did not officially exist, I hope. It is a shock to see that the games not counted on the career stats of the players, and through no fault of their own. Still, our Jim Harley escapes lightly – he does not appear in the LFC players’ sending off list. (Ian Rush was the FA Cup’s top scorer during the twentieth century because Dennis Law’s six goals against Luton in 1961 were expunged after an abandoned game. Law had been Bill Shankly’s prodigy protégé at Huddersfield.)

Meanwhile, did other sports follow suit? The shortened cricket season has left the players’ stats from the pre-war matches unaffected in Wisden. The Rugby Union Football Museum has no record of the pre-September 3 games being no longer counting against players’ records. Rugby League is even more favourable towards its players, as all 1939/40 matches, even in wartime, are deemed to be official, counting towards a player’s career. I sense their opinion of football’s policy on the matter is somewhat disparaging!

In September 1939, the Home Office stopped further football and many other sports, but clearly, only football is believed to have expunged its own records retrospectively, and without any good motive that I can discern. No one seems to have benefitted from the decision. I can only conclude, though always open to correction, that there has been a misinterpretation of the ‘suspension’ of the 1939 season, and an assumption that the word must have encompassed the whole season.

The episode also suggests a lack of protocol for football seasons, or games, being abandoned so that, for example, some uncertainties which threatened LFC’s 2020 title during Covid could have been avoided. (Once more, the government put people’s safety above the season’s integrity as they will have to when the next pandemic arrives; the 2019/20 season survived only by a vote of the FA.) A lack of detailed planning evidently continues to the present day, with the abandoned Blackburn v Ipswich match of 21 September 2025. In this case there is a novel development in relation to ‘null and void’, in that the red card stands, but not the goal scored. (‘The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interrèd with their bones.’) Surely, if an abandoned match is to be expunged, both goal and red card should be equally treated.

Better still, there should surely be some official way to recognise the part played by everyone in matches which are abandoned or void, together with an explanation for having replays. Hopefully, this might involve a rethink about the way 1939/40 players have been treated. Is it too much to hope that the events of 1939 in our football records could be included, though suitably marked as an aborted season entry? It probably is too much to hope for the simplest solution - that the three games can be restored to their original, official status, with 1940 a blank in the list of title winners.

Copyright - Dr Colin D. Rogers for LFChistory.net